Tech and the political power of storytelling

Contents

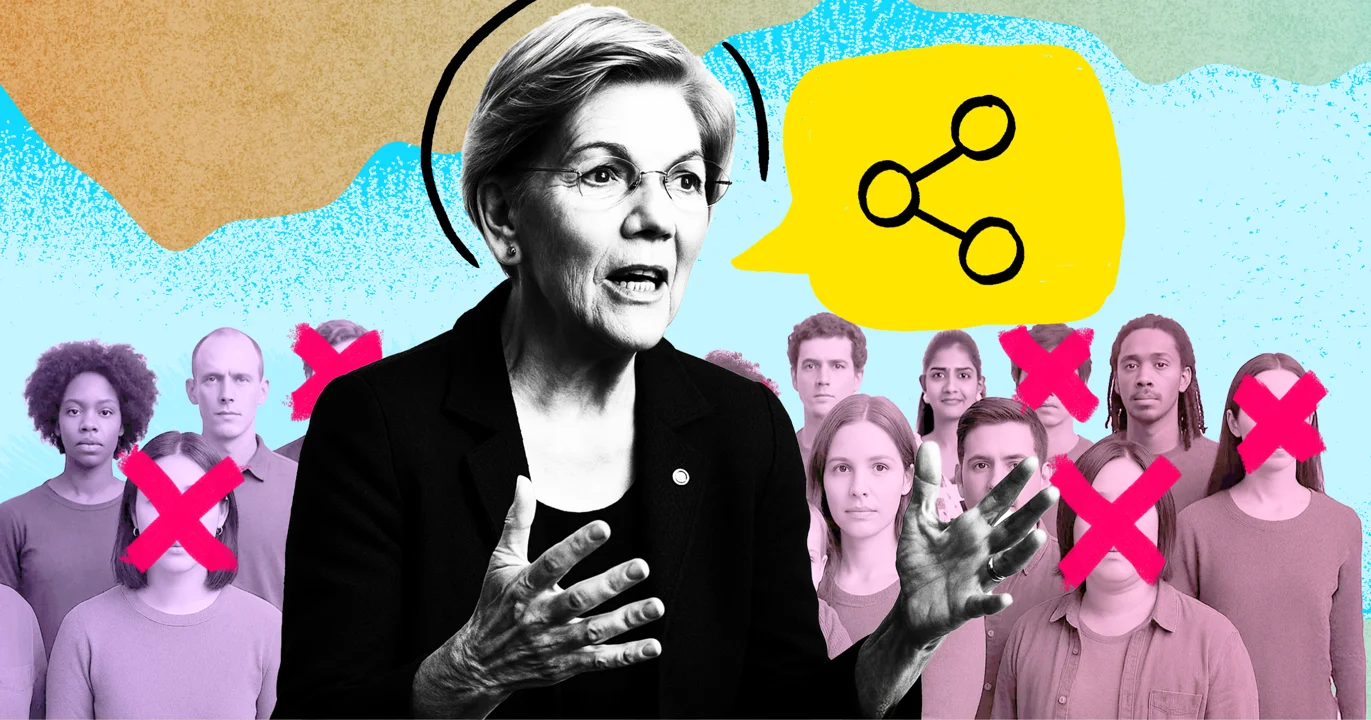

While campaigning to be selected as the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate for the 2020 US election, Senator Elizabeth Warren revealed, in a moving post on social media, how she was fired in 1971 from her first teaching job for being pregnant. It was a textbook campaign approach, especially in a highly personalised campaign environment like the US.

However, Warren then took the unusual step of inviting her followers to share their own experiences of injustices, saying that "we can fight back by telling our stories." Nearly 1,500 people responded, many in intimate and emotional detail, in comments to her post.

According to the new book, Story Tech:. power, storytelling, and social change advocacy, co-authored by Dr Michael Vaughan, International Inequalities Institute at LSE, Dr Filippo Trevisan and Professor Ariadne Vromen, this signalled the beginning of a new approach to storytelling in digital politics.

The book explains: "In recent years, many political organisations have started to ask ordinary people to share their stories with them as a form of participation and support, beyond typical requests to donate money or sign digital petitions … large numbers of people seem eager to respond to these invitations to share their experiences. Crowdsourced personal stories have thus joined the repertoire of digital grassroots advocacy."

Storytelling can galvanise change

But why are personal stories so powerful compared with well-crafted political rhetoric?

Dr Vaughan says: "Storytelling is innate to us as human beings – stories help us construct our social world and imbue it with meaning. For political organisations, stories have particular power compared with facts and statistics. They invite audiences to identify with some characters and not others, and can convey complex causal relationships. All that helps create a simplified version of reality with moral and emotional stakes for the audience.

"When the stories are ‘real’, they carry the power and authenticity of personal testimony. Even though storytelling in politics has a long history, arguably it is increasingly relevant in an information environment where attention is scarce and scepticism about facts is high."

The book explains that "the act of telling persuasive stories has roots back in preliterate oral traditions, and its basic relationship with human psychology has fundamentally remained the same for thousands of years."

Storytelling has long been used by workers’ unions and social movements to galvanise support for change: for example, in the US civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Since the mid-2000s, politicians have also shared more of their personal stories as a way to enhance their appeal and authenticity.

But in recent years, organisations have moved from professionally produced content to large crowdsourcing operations that collect personal narratives directly from supporters and integrate them in their campaigns.

Political organisations have started to ask ordinary people to share their stories with them as a form of participation and support.

The role of algorithms and AI tools in disseminating stories

The book explores the increasingly influential impact of technology: a hidden world of what it calls "story tech" and "story banks" in collecting and using these stories. Databases, story submission portals, algorithms and AI tools are used to acquire, organise, select and disseminate stories at scale in what the book calls the "datafication of storytelling".

Dr Vaughan explains: "One of the drivers of this book was the growth of so-called ‘story banks’ in advocacy organisations. Lots of us will have seen political organisations ask supporters to ‘share their story’, such as by filling out a form on their website. The back end of that crowdsourcing process might be a story bank – sometimes vast databases of personal stories, which organisations archive and catalogue in anticipation of some kind of future use.

What kind of stories do we hear? The hidden risk of "story banking"

There are some risks to this approach, highlight Dr Vaughan and his co-authors.

He says: "The process by which stories get selected for use from these archives is mostly opaque and often defaults to imagining audience preferences. This can result in a kind of storytelling which presents itself as authentic and grassroots, yet involves lots of curation and constraints on what kinds of stories get told.

"Story tech often works to make itself as invisible as possible, but we want to show that it is actually a complex layer of systems and agents with real impacts on what stories ultimately get shared."

This means that the voices of marginalised groups are potentially in danger of being excluded rather than amplified, says Dr Vaughan.

The voices of marginalised groups are potentially in danger of being excluded rather than amplified.

How story banking is helping politicians

"Story banking, however, also has some clear strengths," continues Dr Vaughan. "It enables a potentially meaningful form of participation by large numbers of people. It can equip advocacy groups with lots of content, which can potentially be tailored to specific communication needs, such as targeting a particular area or demographic with a story likely to resonate with that audience, or rapidly responding to media."

The book focuses on identifiable strengths of story banking: successful story-centred campaigns that helped change dominant narratives on disability rights, marriage equality, and essential workers’ rights in the US and Australia.

Dr Vaughan says: "As part of the research for the book, I looked at Australian campaigns for marriage equality and a National Disability Insurance Scheme, both of which were successes in the sense that they secured lasting policy change.

"Storytelling played a big part in both campaigns – not just large-scale collection of stories as a way to mobilise supporters, but using those personal narratives to persuade a wider public by invoking broadly shared cultural scripts around fairness.

"It was this personal storytelling – at scale – which helped galvanise public attention, showed the way policy changes matter to people’s lives, and drew links between individual actions and systemic change."

Returning to personal storytelling increasingly favoured by high-profile politicians, how about UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who repeatedly emphasised that he was the son of a tool maker in his successful election campaign last year?

Dr Vaughan says: "I would say Starmer used a character type to allude to a familiar story. The character is the upwardly mobile working-class kid, and the story is one of upward social mobility and meritocracy – which holds incredible power in broader notions of fairness. The character type functions to distance Starmer from ideas about politicians as detached establishment elites, as well as showing his meritocratic bona fides. Aaron Reeves and Sam Friedman here at LSE have written about the advantage for politicians emphasising working- class roots in their latest book, Born to Rule: the making and remaking of the British elite."

Dr Michael Vaughan was speaking to Joanna Bale, Senior Media Relations Manager at LSE.

AI, technology and society special edition

At LSE our researchers are using technology’s revolutionary power to understand our world better, looking at AI and technology’s potential to do good, and limiting its potential to do harm.

Browse upcoming events, short films, articles and blogs on AI, technology and society on our dedicated hub.

Join us on campus or online wherever you are in the world for LSE Festival: Visions of the Future, a week of special events 16-21 June 2025, free and open to all.

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a world-leading university, specialising in social sciences and named University of the Year by the Good University Guide 2025. Based in the heart of London, we are a global community of people and ideas that transform the world.