Islamophobia Discourse in the US, UK and Australia

This research project maps the political discourse of Islamophobia in Britain, the United States and Australia. "Islamophobia" is a highly contested term, and the political use of it has changed over time and has been different in different places. By exploring the development of Islamophobia as a concept in different countries, this project seeks to answer the question of why different states have responded to the problem of Islamophobia in different ways.

Faculty: David Smith, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney

US Centre Research Assistant: Arundhati Suma-Ajith, International History

Author

Arundhati Suma-Ajith

LSE International History

It's been a really great experience, and I really appreciate ... the Centre's efforts at engaging us throughout the year!

Islamophobia is a complex and intermittent phenomenon; in some arenas it is a product of discrimination used to legitimate existing stereotypes or justify social issues, whilst in others it casts an ominous shadow, working to cause change in the background. The study of Islamophobia discourse is one that seeks to emphasise the latter and delineate societal outcomes as a result of social interpretation that works in the background. Dr David Smith has been working on a project entitled ‘Islamophobia Discourse in the UK, US and Australia', which aims to understand the ways in which Islamophobia has been used by different actors in society. Within this project, my focus has been a collection of British newspaper articles between December 2017 and May 2018. By analysing the use of the term ‘Islamophobia’ within each one, the objective of the project is to understand the way inwhich Islamophobia is framed by different British media outlets, and what implications this has.

Methodology

Drawing on Erving Goffman's Frame Analysis (1974), frames can be defined as ‘mental orientations that organize perception and interpretation.’ Frames are problem-solving schemata, used for theinterpretative task of making sense of situations. They are based on past experiences of what workedin given situations, and on cultural templates of appropriate behaviour. Ultimately, frame analysis isabout how cognitive processing produces an interpretation. This study uses frame analysis to better understand the use of the term Islamophobia in British media. By exploring the processes involved in the making of meaning and influence among elites inside and out of government, in the media and the public, the manifestations of Islamophobia throughout society can be better understood. Each article situates the term ‘Islamophobia’ within an identity frame – race, religion, foreign nationality, pairing another minority, and within a specific substantive frame – the Muslim experience of Islamophobia,an accusation of Islamophobia, contestation over the existence of Islamophobia, pairing it with otherevils like racism and/or anti-Semitism, and extremism surrounding Islamophobia.

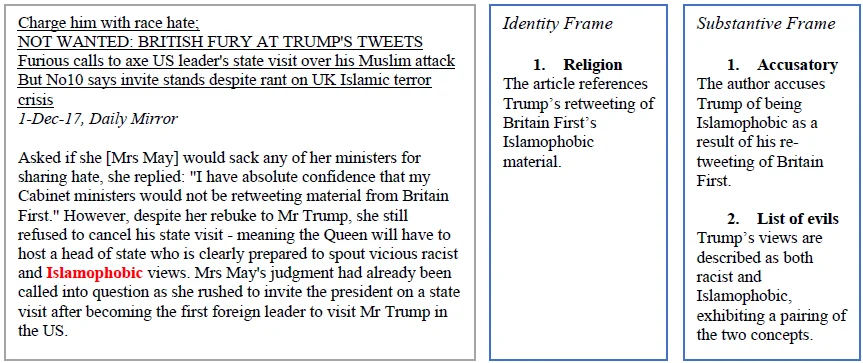

For example, consider the following extract from a Daily Mirror article in 2017. The frames are identified surrounding the use of the word ‘Islamophobic’.

Analysis on this excerpt reveals that Islamophobia has been framed in terms of religion in order toaccuse a foreign head of state, whilst enhancing the message by pairing Islamophobia with another type of discrimination.

Results and some Conclusions

The collection of newspaper articles analysed for this study reveal some general trends:

Islamophobia as a tool of denunciation

The high coincidence of the ‘list of evils’ frame with the ‘accusatory’ frame reveals that expressing condemnation of a group or individual is enhanced when an accusation of one kind (e.gIslamophobia) can be paired with another (anti-Semitism, racism, xenophobia etc).

Muslim experience as a call to action

References in the media to ‘the Muslim experience of Islamophobia’ – often including detailed attacks recounted by individuals – are commonly connected to a ‘call to action’ against Islamophobia and its effects on the integrity of multicultural communities.

The linkage between Islamophobia and extremism

Both Islamic extremism and right-wing extremist responses to it have been linked with the use ofIslamophobic rhetoric. On the one hand, there is a penchant for understanding right-wing extremist responses in terms of ‘anti-Muslim propaganda’ and a process of brainwashing; this can be contrasted with Islamic extremism which is suggestibly a product of Islamophobic rhetoric.

These insights build on existing research by introducing an additional variable – the newspaper itself i.e political leaning, geographical position, authors etc. This allows for a deeper understanding ofmeaning-making and influence from those media outlets that subscribe to different political views. Once this data is consolidated, a more nuanced understanding of the implications of media framing can be achieved.

Islamophobia and state policy

Legislative change has occurred as a result of the greater emphasis on Islamophobia in discourse.When legislation prohibited discrimination on religious grounds in the UK, it sparked greater efforts for the recognition of hate crimes against religious groups. For instance, the Runnymede Trust’s original focus on discrimination has shifted to a new focus on hate crime. Hate crime statistics and Tell MAMA are the government’s evidence of strengthening its fight against Islamophobia. In the US, the election of Donald Trump has polarised politics on a range of issues, of which religious andracial discrimination are an integral part. The fact that hate crimes are rising is a phenomenon thatrequires further investigation; Islamophobia discourse provides insight into this, delineating the sources of discontent, and thus action in both the Islamic and non-Islamic camps. Whether it is the banning of minaret construction in Switzerland and the Muslim immigration ban in America, orgenerally increasing civilian violence, Islamophobia discourse deepens understanding both within and across societies.

Please note that this report gives the views and findings of the Undergraduate Research Assistant, and may not necessarily reflect those of their faculty supervisor, the US Centre or the London School of Economics.