In the wake of COVID-19, the governance of cities has become an increasingly contested political and media space. The first female governor of Tokyo, Yuriko Koike, has boosted her status as potential prime minister of Japan due to her effective stewardship of the pandemic. Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris, has won support for a second term in part due to her handling of the crisis. Before COVID-19, the former mayors of Buenos Aires and Mexico City built up formidable political bases to become presidents of Argentina and Mexico. Boris Johnson fulfilled his lifelong ambition to become Prime Minister of the UK by using London’s City Hall as a stepping stone. Five mayors of French cities have become presidents in recent decades, with Jacques Chirac moving directly from Paris’ Hotel de Ville to the Élysée Palace.

Cities concentrate people, voters, jobs, and money. They often outperform their national contexts in productivity, wealth creation, and social mobility. As such, they are viewed with antagonism by national leaders. But they also act as platforms for a career on a bigger stage. They can be launching pad for a meteoric political rise.

This trend has fuelled a quasi-messianic belief that ‘if mayors ruled the world’, the world would be a better place. Major philanthropies support city networks and training programmes that believe national problems are urban problems that can be addressed locally by well-run, effective city administrations. The historian David Runciman has recently poured cold water on this claim, reminding us that city governments still rely on national governments ‘to underpin their finances and to secure their authority.’

At one level, he is right. Cities cannot operate on their own in a globalised world, nor can they oversee issues that transcend urban boundaries. Defence, diplomacy, regional connectivity, and trade can only be set at a national scale, often in dialogue with regional and international partners. While cities can and do contribute to job creation, social equity, and air quality, they can’t do it on their own.

While there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution, some forms of urban governance are far more likely to ensure greater stability, equity, and sustainability than others. Firstly, a directly elected mayor, leader, or governor, who is accountable to the electorate on a fixed-term basis, is a prerequisite for balanced governance. Secondly, the city authority should have jurisdiction over the widest ‘functional’ built-up area where the majority of the voting population lives and works. Thirdly, the city authorities should have the powers to raise funds through local taxes, bonds, hypothecation, or other fiscal initiatives for projects and investments that directly affect the quality of life and the environment of residents. Fourthly, urban leaders should have the mandate to set out a vision for a long-term development plan that integrates spatial planning with clear economic, social, and environmental objectives.

None of these conditions per se guarantee perfection. Corruption, mismanagement, inefficiency, and voter fatigue can disrupt forms of governance that have worked well for generations. But it is the interrelationships between these systems and different tiers of government which can determine success or failure. As the COVID-19 crisis has shown, there are wide disparities on what powers city mayors actually have and how easily they can conflict with or be overridden by regional bodies or national governments.

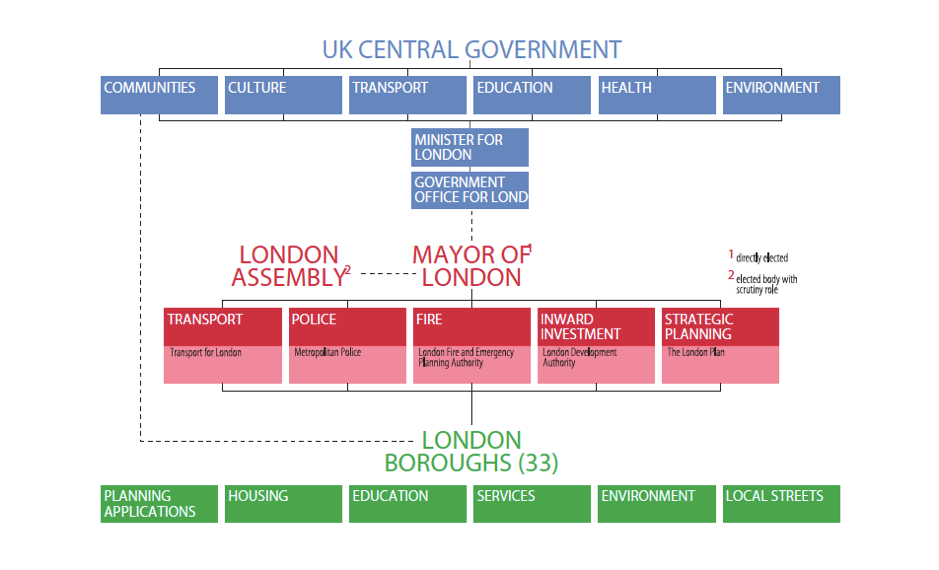

President Macron of France, for example, can issue orders for schools to reopen. But it is up to the Mayor of Paris – who controls the city’s public school system – to take the final decision. Not so in London, where the national government's education policy bypasses the mayor to directly influence borough-operated school districts.

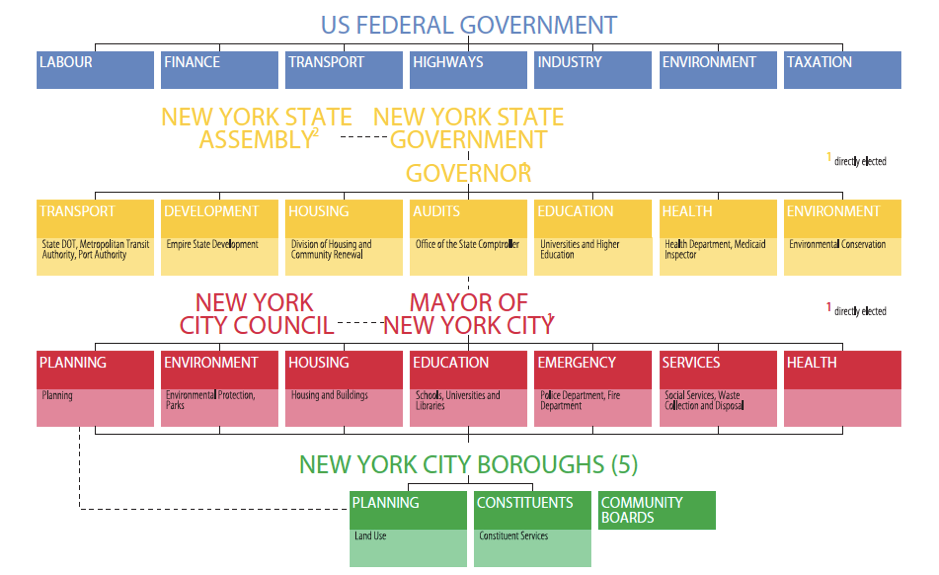

Competition between local and national governments is not unique to COVID-19. Control over city budgets, public transport, policing, housing, economic development, and education have long been hotly contested between central, regional, and metropolitan authorities. Despite having a powerful mayor, London’s budget is effectively set by central government, and the Prime Minister can impose stringent top-down rules on how much Londoners should pay to use their public transport system. Nonetheless, the mayor does control Transport for London, while New York City’s equivalent (the Mass Transit Authority) is managed and funded by the State of New York rather than the city’s mayor. In Europe, the pattern is equally varied. German cities are strongly controlled by regional länders. Barcelona, meanwhile, is more accountable to the autonomous regional government of Catalonia than to the Spanish Government in Madrid.

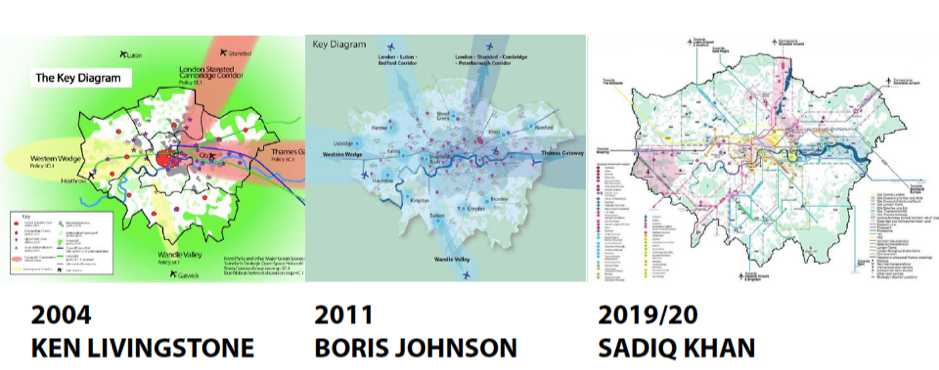

In the debate about how best to govern cities, London is of special interest as it celebrates the twentieth anniversary of the introduction of an executive, directly-elected mayor. It was a bold and innovative move. A recent review by the Centre for London notes that ‘since 2000, London’s three mayors have shown themselves to be able advocates for the capital, leaders at times of crisis, and promoters of projects and policies that would have been impossible in the 1990s, like congestion charging and cycle hire schemes. Their powers have been extended to affordable housing programmes, more comprehensive planning powers, and stronger police oversight.’

Much to the chagrin of other English cities, London has benefitted from billions of pounds of public investment in its infrastructure over recent decades. This may be partially due to lobbying skills of individual mayors, but the certainty provided by the London Plan, a strategic development document periodically published by the Mayor of London, has proved fundamental as well. It has facilitated investment from central government to support London’s pivotal role in the national economy. The London Plan would be ineffective if it did not cover the entire functional, built-up area of Greater London and its authority was not supported by central government.

Having a powerful mayor who might scale the heights of national politics may be an asset, but institutions that enable territorial control over the entire built-up area under the jurisdiction of an elected urban leader remain critical to a city’s long-term sustainability.

Ricky Burdett is the Director of LSE Cities and Urban Age and a Professor of Urban Studies at the London School of Economics

Recent Interview with New London Architecture: https://nla.london/videos/livingstones-london