Minimum wage increases lead to faster job automation

Minimum wage increases are significantly increasing the acceleration of job automation, according to new research from LSE and the University of California, Irvine.

Analysing US population data from 1980-2015, researchers found that a 10% increase in the minimum wage leads to a 0.31 percentage point decrease in the share of automatable jobs done by low-skilled workers overall. The effects are largest in manufacturing: a 10% increase in the minimum wage leads to a 0.73 percentage point decrease in the share of automatable jobs done by low-skilled workers. Researchers found that older workers are affected more than younger workers, and black workers are more affected than white workers.

Dr Grace Lordan of LSE's Centre for Economic Performance and Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science said: "Our research tells us that minimum wage increases are now shaping the type of work low skilled people do by accelerating automation. It also implies that the skills needed for low wage jobs are changing."

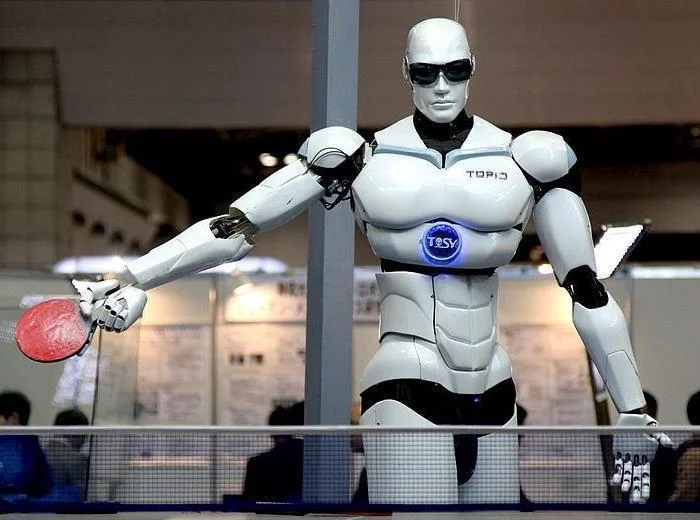

The authors give examples of how technology is replacing workers: supermarkets can substitute self-service check-out for cashiers, and assembly lines in manufacturing plants can substitute robotic arms for workers. The authors also note that at the same time, firms may hire other workers who perform new tasks that are complementary with the new technology. For example, a firm using more robots may hire individuals to service, troubleshoot, and maintain these new machines. However, these jobs require different skills to the jobs that they are replacing.

The researchers conclude that workers more likely to be replaced following minimum wage increases are those who are low skilled, earning wages affected by increases in the minimum wage, while workers who "tend" the machines are higher skilled. This suggests that there is a potential for labour reallocation away from jobs that are automatable following increases in the minimum wage.

Data was taken from the Current Population Survey in the US. Because each state in the US sets its own minimum wage, increasing it at different times, this enabled researchers to compare how technology has been advancing over time at a differential rate in each State.

Overall, the US analysis shows that higher minimum wages causes substitution away from people doing routine tasks, among low-skilled workers. But there may also be reallocation of these low-skilled workers to less automatable jobs. So, the authors also look at whether a higher minimum wage increases transitions to non-employment among low-skilled workers who were in automatable jobs.

Dr Lordan added: "From this analysis we show that the negative effects on employment shares in automatable jobs are associated with job loss and transitions to non-employment among low-skilled workers who were initially doing automatable jobs. These effects are again larger for those older than 40 years and younger than 25 years, as well as Black individuals."

The authors also find evidence that minimum wage increases make it more likely that low skilled workers in automatable jobs change jobs and work fewer hours. Given the number of U.S. states that have laid out plans to increase minimum wages significantly over the next five years, overall the work highlights new evidence suggesting that these sharp minimum wage increases will shape the types of jobs held by low-skilled workers, and create employment challenges for some of them. The authors also emphasis that technological advances mean that more jobs will be automatable in the future.

People versus machines: the impact of minimum wages on automatable jobsby Dr Grace Lordan of LSE and Professor David Neumark of UCI is published in the latest edition of Labour Economics.

In her associated work for the Low Pay Commission, Dr Lordan has also found similar stylised facts for the UK, however the effects are smaller. In this complementary work drawing on a review of Google patents, Dr Lordan writes that there are three distinct classifications of low skilled jobs that are useful when framing the future:

- The first, are jobs that will not be fully automatable in the decade, given that they require human interaction in an unpredictable sequence of actions as well as empathy from the provider. These low skilled jobs include childcare and hairdressing.

- The second type are jobs where human interaction may not be part of the value of service to customers on some occasions, and there is a definite sequence of actions that can be codified. Examples include wait staff and bar tenders. She expects continued attempts to automate these jobs, with a polarization by quality where some jobs are provided by humans and others by robots.

- The third are jobs where customers care less about whether or not the work is carried out by a human, and innovation for robotic substitutes has made good progress. Examples include delivery driver or security guard. This is the group of jobs which is the most at risk of disappearing.

Dr Lordan emphasises that jobs lost to automation will certainly be met with the creation of new jobs that require a different set of skills. Given her research she thinks that older low skilled workers may be the biggest losers as they may not get so many opportunities to retrain.

She said: "We do not know if the new low skilled jobs created will be in equal number to those lost. Just because all jobs lost have been replaced with new jobs in the past does not mean that this will continue to occur in the future. Replacement becomes less likely as machines continue to learn and minimum wages put pressure on companies already operating in highly competitive environments with tight profit margins, like transport, services and retail. So, there is a role for policy in the ongoing monitoring of trends, and to consider how the rents earned by machines should be re-distributed within society as technology adoption accelerates."