Creating an Incel: memes, hackathons and the perpetuation of gendered inequality online

Contents

There probably isn’t an internet user among us who hasn’t shared a meme at one time or another. Since the birth of social media, memes have become a popular way to communicate, share a humorous message and a frivolous moment of light relief. But behind the jokey façade, has the meme become a vehicle that propagates stereotypes and views that would be considered, in other formats, unacceptable?

Dr Siân Brooke,a researcher in the Department of Methodology at LSE, argues that the meme is anything but powerless. Her research into the ways people communicate on anonymous forums such as Reddit or 4Chan, and the way coders interact at hackathons, shows that memes have become a powerful way to spread and embed gender stereotypes, helping to replicate the power structures of the offline world online.

A self-taught coder, Dr Brooke has carried out multi-sited ethnographic research at seven hackathons, as well as created online platforms to explore how people interact in an anonymous online setting. She is currently based in Berlin, where she will be spending the year studying, among other things, the interactions of the Chaos Computer Club, Europe’s largest association of hackers.

"Gender Studies and Data Science are not normally disciplines that are that friendly to each other," she says. "But this combination is necessary to understand how toxicity in tech cultures and Incels work, because you need to have an understanding of what sexism looks like within that arena, of how knowledge is gatekept, and how that then moves into this hostility towards women and minorities that we see most clearly with Incels. Also, sometimes it’s as simple as to get the jokes, you need a bit of the technical understanding."

My research looks at the way some memes are being used to spread and normalise sexist and misogynistic views that these men online then start to identify with.

Using humour to spread hate

This understanding is necessary because stereotypes are often spread and strengthened through innuendo and humour, an issue she explores in several papers. "I first started looking at gender in memes and on anonymous forums because I found this notion of how gender works in anonymity to be really interesting," Dr Brooke explains. "Why do people act a certain way? How can anonymous spaces be sexist? And how is gender understood in online communities?"

"Often the sexism in these memes is quite mundane – it’s these soft experiences where if you’re a woman, it’s repeating sexism you’ve encountered elsewhere, where sexism itself can even be the butt of the joke."

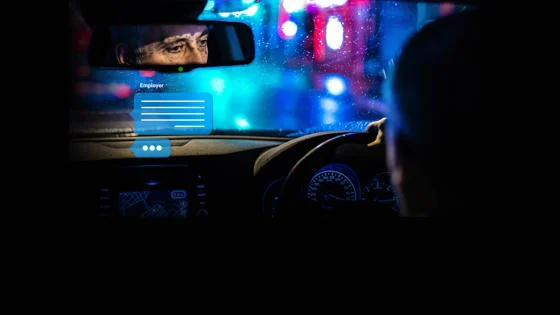

The sexism may often be mundane, but the impact of these online discourses has been anything but, Dr Brooke argues, with memes on chat forums used as a way to establish a hierarchy of gender that has led to a culture of online toxicity. At its most extreme, this has encouraged a rise in men self-identifying as Incels – men who consider themselves unable to attract women – a belief that is accompanied by derogatory and hostile opinions of women.

"Incels have become this violent hate group which is even branded by some governments as being like a terrorist organisation," explains Dr Brooke. "But people don’t start off radicalised, they don’t emerge as an Incel. It’s a process, and my research looks at the way some memes are being used to spread and normalise sexist and misogynistic views that these men online then start to identify with."

Hackathons, memes and gender stereotypes

In her paper "’There are no girls on the internet’: gender performances in Advice Animal memes", Dr Brooke sets out the various gender-based attitudes found in memes shared on the r/AdviceAnimals forum of Reddit. Her study of a cross-section of memes submitted to the forum reveals an uneven power balance in the way that men and women are portrayed – overwhelmingly, she documents, male characters are the default central character, portrayed as speaking sense, while women are portrayed as highly sexualised, obsessive and clingy.

These attitudes were also clear at the many hackathons where Dr Brooke conducted research. These social coding events provided the perfect environment to study how these images were spread and normalised, revealing how gendered memes provide a way for coders to bond and connect, with conceptions of gender being central to socialising at these events.

Those who identify as Incels and promote this particular view of masculinity, they also all have this … belief in their technical superiority.

"In my paper ‘Nice guys, virgins and Incels’, I look at references to Incels and the humour they use, and the derogatory way they talk about women – as sexual objects who aren’t able to have anything to do with computers – and how all of these views are also found in programming more generally," she says.

"The idea that a good programmer is a man who is unable to attract women is both based in sexism and compulsory heterosexuality. One thing I find is that because these forums are built around the notion of technology, those who identify as Incels and promote this particular view of masculinity, they also all have this idea of technical competence, a belief in their technical superiority. My research explores how the vocabularies of technology culture can be found both off- and online, and particularly in memes. I found that even the mundane memes about technology culture revealed the toxic masculinity and ideology of the Incel."

The meme, she argues, has become a tool for male coders to establish and maintain their power – an art form that perpetuates derogatory gender stereotypes and attitudes.

If you’ve become very popular on a site known for its misogynistic content … you’re not going to be very supportive of the complete opposite approach.

Equality online requires equality offline

With coding and technology still very much a male-dominated industry, tackling harmful online gender stereotypes won’t be easy. Diversifying the workforce could be one way to start to challenge these age-old stereotypes around women and technology.

As a coder herself, and teacher of Computer Programming and Machine Learning courses at LSE, Dr Brooke agrees. "More women in programming would help, including as teachers," she says. "That’s good for everyone as it normalises the idea that women can code as well as men and may dampen some of the more stereotypical assumptions.

"Having said that, when people often look at women's inclusion in technology, they often start at a point which neglects women's agency to decide to just not be harassed. Women have the right to think ‘yeah, I would love to do it, but I also don't want to deal with a bunch of Incels. I’m not going to opt into that.’ And so it's not necessarily always that women are being pushed out through fear. The decision not to go there can almost be like a form of protest – to decide not to do it."

Ultimately, Dr Brooke argues, if we are to ensure a truly diverse and equal experience for people both using the internet and working in the tech world, policing what people post online will not address the root of the problem. It is in the offline world where these issues need to be addressed.

She cites moderation – currently the main way sites are attempting to keep themselves clear of unacceptable views – as a prime example. "If we look at Reddit and Stack Overflow (a popular programming Q&A forum) for example, someone who uses the platform a lot will have a greater status and more ability to remove problematic posts than someone new to the site. But that just helps maintain the status quo," she explains.

"These sites are very male-dominated and very masculine in terms of their voice, and currently it’s the people who have succeeded on these sites that have the power in terms of moderating content. If you’ve become very popular on a site known for its misogynistic content or proliferation of negative stereotypes or outright sexist and violent speech, you’re not going to be very supportive of the complete opposite approach."

"So while there are tools and ways we can moderate within the technical system, we’re not going to be able to engineer an ideal online society or create a very particular and specific use of technology which will solve these – particularly because people have been consistently proven to be extremely good at using technology in a way that it wasn't actually intended to be used," she says.

"These problems, and this idea that people are becoming more polarised, has existed for as long as the internet – but it's not a uniquely online problem. Ultimately, we need to address these issues as a society in an educational way, which, unfortunately, is a lot more expensive."

There may be no silver bullets or technical solutions to tackling cultural prejudice, but insights into the ways these messages are seeded and spread are vital if we are to ever ensure an online world where prejudice and hateful rhetoric do not thrive.

Dr Siân Brooke was speaking to Jess Winterstein, Deputy Head of Media Relations at LSE.

Download a PDF version of this article