Race and the platform economy

Contents

Imagine you’re in work one day when your boss says you’ve done something wrong and they’re going to have to sack you. They can’t tell you what you’ve done, when it happened or how the decision-making process was made.

This might sound like something out of a Franz Kafka novel, but this has been the frightening reality for many platform economy workers who have been excluded from their main source of income with no explanation.

"I have seen multiple grown men in tears telling me how devastating it is to fight for their livelihoods with what is essentially an automated messaging system. This can be particularly distressing if English isn’t your first language or you don’t have a grip on the complex bureaucratic institutions that make up the UK," explains researcher Dalia Gebrial.

A lot of the workers on these platforms tend to be from migrant or racialised minority backgrounds and previous research has suggested this makes it easier from them to be exploited.

Racialisation of the workforce

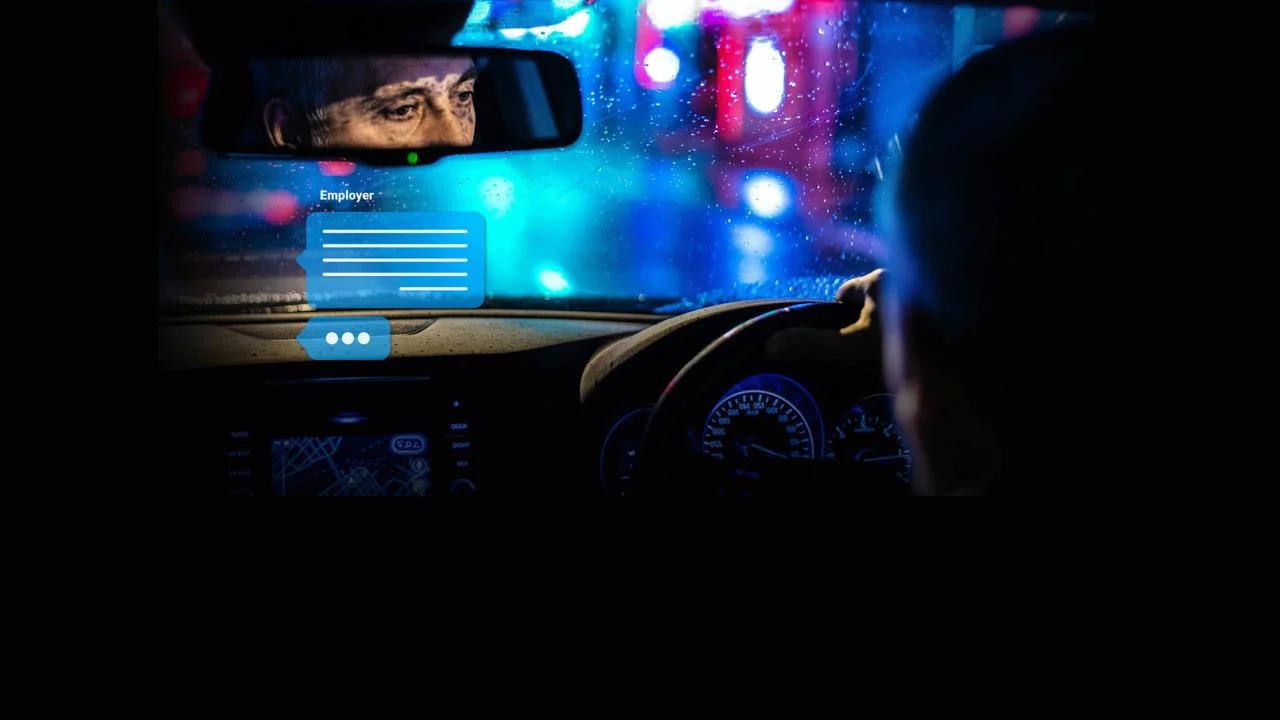

Based in the Department of Geography and Environment at LSE, Dalia Gebrial’s work focuses on race and gender in the platform economy. Often managed through algorithms on phone apps, platforms "matchmake" people who require a service (such as a car journey or food delivery) with those who can provide it. Popular platforms include the ride hailing app, Uber and the takeaway service, Just Eat.

With Uber and the babysitting app Bubble as case studies, Dalia Gebrial is using a variety of methods to explore what life is like for platform workers. These include interviews with workers; observing them in areas where they congregate (such as train stations in the case of Uber drivers); and text and image analysis of apps. Although ongoing, her research has already uncovered some unsettling realities.

"A lot of the workers on these platforms tend to be from migrant or racialised minority backgrounds and previous research has suggested this makes it easier from them to be exploited. I’m interested in homing in on this observation and looking at the racialised element of this work. Why have these platforms become so successful? And how is the racialisation of the workforce coded into the political and economic context but also into the technology itself and its algorithms?"

The terms "racialise" and "racialisation" refer to the political process of ascribing ethnic or racial identities (and associated stereotypes) to groups, which then reinforce and perpetuate inequalities and social exclusion.

[It’s] an incredibly brutal process. It creates a scenario in which workers almost become part of the machine, and by becoming part of the machine they become dehumanised.

Becoming part of the machine

Dalia Gebrial’s work has revealed that key technologies introduced within platforms are having problematic consequences. For example, interviews with workers have revealed concerns about the ratings system used by many apps. Immigrant and racialised minority workers often report feeling worried about ratings, leading them to dress and speak in certain ways. In comparison, white workers tend to be more relaxed about them – believing a friendly attitude is sufficient to achieve a good score.

Information asymmetry built into many of the apps is also a major problem. This is where the platform holds information about a worker that is not available to them. This allows situations to arise where workers can be automatically deactivated from an app based on undisclosed algorithms without ever having an interaction with a person or the right to a fair disciplinary process.

One worker Dalia Gebrial spoke to recounted how he was locked out of Uber for three months after failing a facial recognition check from the app. Designed to ensure only the licenced driver is using the account, facial recognition software is known not to work as effectively on darker skin tones. In this case, the driver had experienced an eczema flare-up which made his skin appear darker than his original picture. Although he was reinstated on the app after three months, he wasn’t compensated for the loss of wages during that time.

"Many of these workers don’t have savings, so this is an incredibly brutal process. It creates a scenario in which workers almost become part of the machine, and by becoming part of the machine they become dehumanised," she says.

Platforms will always find ways to exploit the fundamental conditions that have given rise to them in the first place – such as draconian immigration policies or the legacy of the war on terror.

Changing the broader environment

So, what can be done to support workers? Dalia Gebrial believes the February 2021 Supreme Court judgement that Uber drivers should be treated as workers rather than independent contractors is a hard-won step in the right direction. This ruling means drivers are now entitled to holiday pay and minimum wage but, as Dalia Gebrial argues, the apps can often get around these rulings – tweaking their business models so they can continue as usual. Without changing the broader environment in which the apps operate, not much will change within them.

"Making legal challenges to individual companies is important as it gives institutional acknowledgement to the situation. However, the problem is much bigger than the platforms themselves, it’s about the way our economy is designed - and particularly how this has manifested since the 1970s. Platforms will always find ways to exploit the fundamental conditions that have given rise to them in the first place," she says.

With the platform economy looking like it’s here to stay, understanding how workers are impacted is an important step towards improving conditions and the wider environment in which workers operate.

Dalia Gebrial was speaking to Charlotte Kelloway, Media Relations Manager at LSE.

Photo by Barna Bartis on Unsplash

Download a PDF version of this article