Cultural stereotypes of multinational banks: how biases spread and affect bank lending to governments

Contents

Financial markets, even more than other markets, run on trust and stumble in its absence. Complete contracts accounting for all conceivable contingencies are a textbook abstraction, while adjudication by courts is time consuming and unpredictable. For individuals and institutions to engage in transactions, their counterparties must be trusted.

This is why one often observes a concentration of commercial and financial transactions among individuals with a common cultural background, who share extra-economic links, values and trust. It is why investors, despite advances in technology leading to a proliferation of statistics and other hard information, nevertheless tend to underweight culturally distant foreign markets while overweighting firms whose CEOs share a common cultural background.

These considerations apply with special force to international investments, and to investments in the bonds of foreign government in particular. Such sovereign bonds are incomplete contracts - their covenants do not make provision for all conceivable contingencies, such as political events, economic shocks and global pandemics, that may affect a government’s willingness and ability to pay. When borrowers and lenders are of different nationalities, legal proceedings may involve multiple courts, whose jurisdiction is uncertain. Governments enjoy a degree of sovereign immunity, casting doubt on the existence of a judicial solution to a default.

Such considerations heighten reliance on the perceived trust of foreign nationals and their government as an alternative to legal contract enforcement. Sovereign bonds tap into these cultural stereotypes in that they are directly associated with a national government and a nationality.

As managers relocate from other countries to a bank’s home country, they unsurprisingly bring their cultural stereotypes with them.

How cultural stereotypes may spread within a financial institution

In a new paper, co-authored with Barry Eichengreen of UC Berkeley, we use data on banks’ investments in European government bonds to analyse the impact of cultural stereotypes on cross-border investments. Our findings reveal that when residents of the country or countries where a bank operates regard the residents of another country as relatively trustworthy, the bank in question is more likely to hold bonds of that other country.

To rule out confounding factors - those other potential characteristics across countries that may correlate with both trust and bond holdings and thus may create the illusion that there is a relationship between the two -, we develop a bank-specific measure of trust. Strategic decisions such as whether or not a bank should invest in the bonds of a country are taken at headquarters by members of the bank’s investment committee. But information affecting that strategic decision is assembled by staff stationed in the various countries where the bank operates branches and subsidiaries and transmitted from there to headquarters. The cultural stereotypes of the residents of those same countries will tend to colour that information.

Similarly, such stereotypes can affect how that soft information is received by directors, who may share the same stereotypes given how banks hire and promote internally, including across borders, such that the composition of bank boards and officers reflects the geography of the bank’s branch network. Examining the managerial flows between foreign branches and headquarters of banks in our sample, we are able to provide substantive empirical evidence that, as managers relocate from other countries to a bank’s home country, they unsurprisingly bring their cultural stereotypes with them.

The persistence of cultural stereotypes

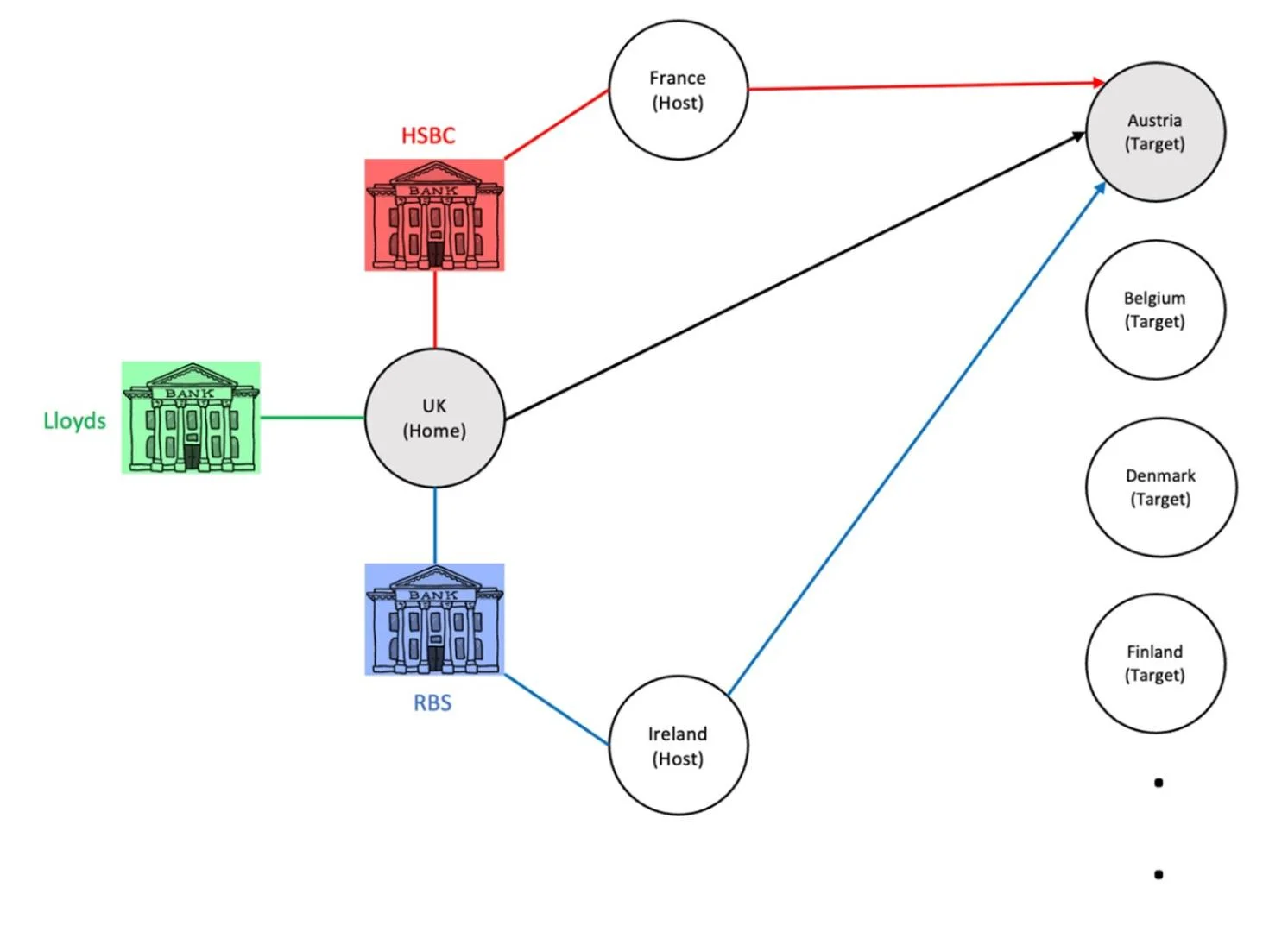

Through focusing our analysis on banks with branches in multiple countries and establishing a model that assigns to branches of a bank operating in a country that country’s level of bilateral trust in other countries, we are able to identify the levels of trust that various banks have in different countries. Figure 1 (below) illustrates our logic with the simple example of UK banks, where we can make a comparison among three banks with different branch networks (ie, HSBC, RBS and Lloyds) at the same point in time while keeping their home country (ie, UK) and target country (ie, Austria) fixed.

Figure 1: Identification Strategy at Bank Level.

Note: This figure represents the identification strategy as described in Section 4 of Eichengreen & Saka (2022).

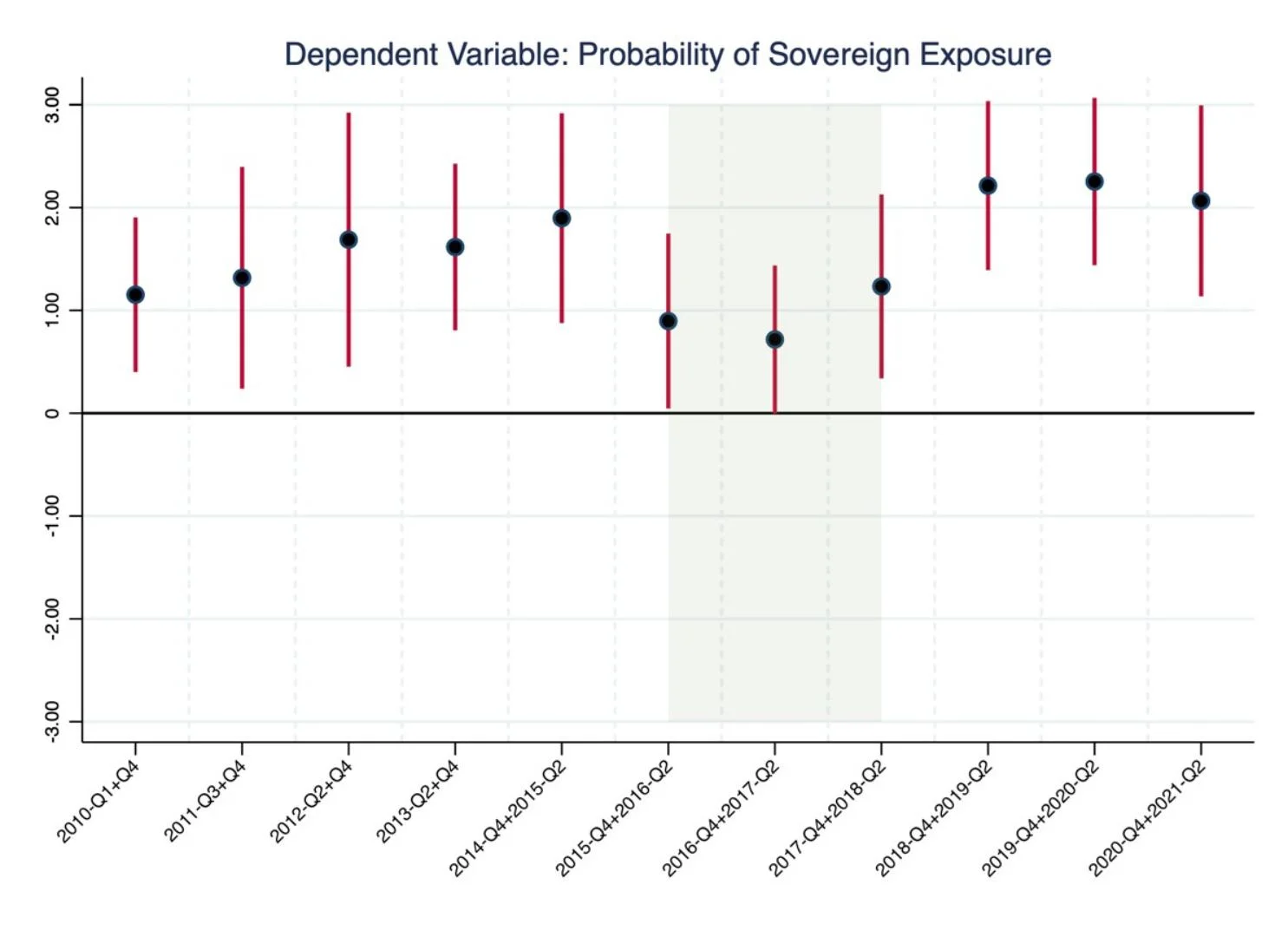

Our findings show that this bank-level measure of trust predicts banks’ decisions of whether or not to purchase the sovereign debt of a country. A rise of nine per cent (ie, one standard deviation in statistical terms) in trust towards a country, we find, increases the probability of the bank investing in that target country by 14 per cent, which is a large effect. Our analysis also reveals that the effect is stable over a sample period spanning more than a decade. As Figure 2 (below) below shows, the effect is not only statistically significant and economically important but also persistent over time, except a brief period during which granularity of sovereign debt portfolios was hampered due to a change in reporting frameworks.

Figure 2: The Impact of Bank-level Trust Bias over Sub-Sample Periods

Note: This figure shows estimates for the coefficient of bank-level trust bias separately for 11 distinct sub-sample periods. Dependent variable is a dummy indicating any positive exposure of a bank toward a target country at a point in time. Shaded areas indicate sub-periods during which EBA reported sovereign exposures based on regulatory FINREP data that restrict the level of granularity disclosed in banks’ sovereign debt portfolios. The specification is Column 5 of Table 3 in Eichengreen & Saka (2022). Only the estimated coefficient on Bank-level Trust Bias is plotted. Confidence intervals are at 90 per cent significance level. Source: EBA, CEBS, Eurobarometer and SNL Financial.

We show further that well diversified, relatively sophisticated banks with the best access to hard information are less likely to use cultural stereotypes as a determinant of their sovereign lending. Moreover, investments in target countries whose bonds are not frequently found in bank portfolios, about which hard information may be relatively scant, are more likely to be influenced by such stereotypes. Finally, we find that the impact of trust is substantially higher for target countries experiencing a sovereign debt crisis, when cultural stereotypes – and thus the role of trust – may become particularly salient.

Our results should also invite multilateral banks to rethink the diversity of managerial teams responsible for cross-country investments.

Cultural biases are likely to distort banks’ investment decisions and impact profitability

Experts in finance tend to characterise the investment decisions of financial institutions as driven by careful evaluation of hard information. We emphasise, in contrast, that the international investment of multinational banks are also influenced by deeply held cultural stereotypes about the trustworthiness of different nationalities. These findings resonate with the experience of the Euro Crisis a decade ago, when Northern European investors asked out loud whether Southern European borrowers could be trusted.

Our findings have important implications for interpreting observed financial-market outcomes. These trust-induced changes in portfolio allocations have nothing to do with the fundamental risk of the target country and simply reflect cultural biases. For this reason, they are likely to distort banks’ portfolio decisions and reduce their profitability.

Our results should also invite multilateral banks to rethink the diversity of managerial teams responsible for cross-country investments. Banks with branch networks that are geographically well diversified and whose management teams similarly are geographically well diversified are less likely to fall into the trap of relying on cultural stereotypes. Diversity in bank management brings in a more balanced view of the potential investments and consequently more efficient portfolio allocation.

"Cultural Stereotypes of Multinational Banks" is by Barry Eichengreen and Orkun Saka. Explore our dedicated hub showcasing LSE research and commentary on the UK economy.

Download a PDF version of this article