What really went wrong in the Middle East

Contents

As the grip of the imperialist European powers loosened in the Middle East in the late 1940s and early 1950s, any hopes in the newly emancipated nations for sovereignty and independence were soon dashed.

Instead, the region became a proxy battlefield for the Cold War being waged between the United States and Russia as they struggled for dominance.

It is through this lens that Professor Fawaz Gerges’s new book, What Really Went Wrong: The West and the failure of democracy in the Middle East, explores the region’s ongoing instability.

He challenges the Western view that the Middle East is "chronically chaotic" and its people "inherently violent", arguing that many of the tensions seen today "are the result of US imperial ambitions to create a Pax Americana - one that the United States is the dominant global power."

The US and the Middle East

"The argument that Arab countries suffer from a special brand of ancient hatreds is particularly heinous because it ignores the role of Western states in contributing to regional fragility and instability," says Professor Gerges.

"Obsessed with Soviet Communism, Washington protected repressive Middle Eastern regimes in return for compliance with American hegemonic designs and uninterrupted flows of cheap oil and gas. And all this while preaching ‘freedom and democracy’ at home," he adds.

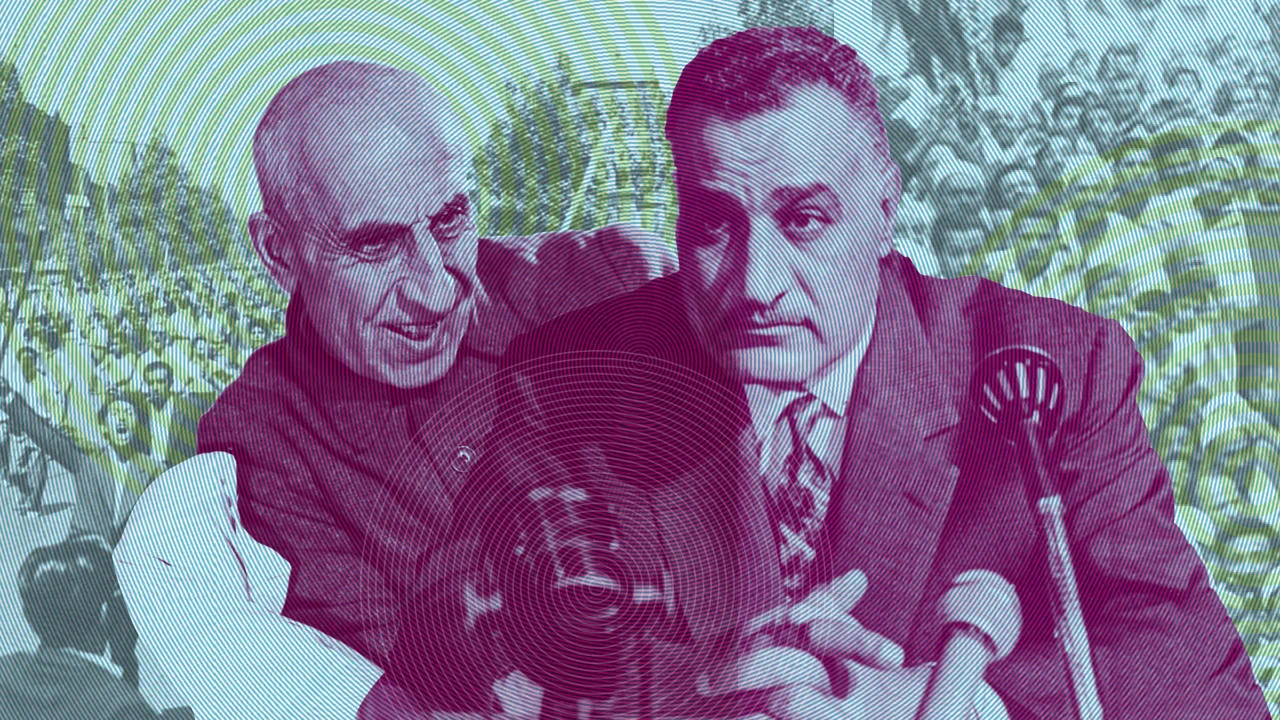

In Iran, for example, the government of the democratically elected Muhammad Mossadegh was overthrown in a coup backed by the United States’ and Britain’s intelligence agencies.

Mossadegh had come to power in 1952 with an overwhelming majority – winning nearly 90 per cent of the votes in parliament. A moderniser, he pushed for a judiciary independent of government influence, promoted free elections, and defended freedom of religion and political affiliations.

Mossadegh was seen by many as a man of personal integrity and honesty who was careful to avoid the appearance of nepotism or corruption. Educated in Europe, he was largely pro-Western and had a benign view of the United States. He was far from a Russian sympathiser, but he was also a nationalist and anti-colonialist who believed in his country’s economic sovereignty.

Mossadegh sought to use the revenues from Iran’s resources to benefit its people, leading him to nationalise the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), much to the ire of the British who owned a golden share in the company. The AIOC’s oil concession provided cheap oil to Britain, including its navy, at a price which was highly disadvantageous to Iran. Britain responded by trying to destablise Mossadegh’s government through a global Iranian oil embargo and even state-sanctioned sabotage against a major oil refinery in Abadan.

The overthrow of Mossadegh jettisoned a potentially positive model for the region, paving the way for the eventual emergence and spread of radical and revolutionary ideologies like Marxism and Islamism.

Propaganda, coups and concern over Soviet Russia

Then, in 1952, Britain’s MI6 surprised the CIA with a plan for a joint paramilitary operation to depose Mossadegh from power – this was initially rebuffed. The US was also against the nationalisation of Iranian oil because of the precedent it set, but felt that the British could be more accommodating of the growing nationalist aspirations in the newly decolonised world.

However, as fears about the influence of Communist Russia in Iran increased, and President Dwight Eisenhower replaced President Harry Truman in the White House, the US position shifted.

The CIA began a programme of propaganda against Iran’s Prime Minister. Along with MI6 operatives, they sullied Mossadegh’s reputation by bribing journalists, politicians, street thugs and army officers.

On their second attempt they successfully engineered a coup against Mossadegh and centralised power under Iran’s monarch, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. The autocratic Shah denationalised oil, crushed all political dissent and widened social inequalities through his economic policies.

Extraordinarily, it was the US which helped him to create the secret police force, SAVAK. This censored the media, screened applicants for government and academic jobs, and used brutal methods of torture and summary executions against anyone who fell foul of the Shah’s oppressive rule.

"The overthrow of Mossadegh jettisoned a potentially positive model for the region, paving the way for the eventual emergence and spread of radical and revolutionary ideologies like Marxism and Islamism. It also gave momentum to the Islamic clerics who seized power in 1979," argues Professor Gerges.

"If the results in Iran were tragic, the ramifications for the United States were also spectacularly counterproductive," he adds.

If the results in Iran were tragic, the ramifications for the United States were also spectacularly counterproductive.

The US and Egypt

Like Mossadegh, Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser saw the United States as a potential force for good, in contrast to the imperial powers in Europe. He too would be sorely disappointed by Washington’s squandering of this goodwill.

Nasser ascended to power rapidly, rising from a military officer to the top of the political ladder following the 23 July 1952 coup d’état, which saw King Farouk toppled by a group of revolutionary Egyptian nationalist officers known as the "Free Officers".

Nasser prioritised the expulsion of British forces which had occupied Egypt since 1882, favouring modernisation and aiming to lift millions of people out of poverty.

Nasser was no democrat, but he initially had good relations with the US. He was not attracted to communism because, as a Muslim, he was not interested in communist atheism, and he also wanted Egypt to be independent of outside interference. He believed instead in Pan-Arab nationalism – the unity of Arab nations.

However, a turning point came when, in 1955, Israel launched a crushing attack on Egyptian troops in Gaza in response to the murder of an Israeli civilian by a terrorist found to have links with Egyptian military intelligence.

The attack revealed the Egyptian military’s weakness and came shortly after the signing of the Baghdad Pact – a defensive organisation for promoting shared political, military and economic goals – by Turkey, Iraq, Britain, Pakistan and Iran.

Eisenhower officials now saw Egypt as the rising power in Arab politics and Nasser as a tough and disruptive actor to be reckoned with.

Egypt turns to Soviet Russia

In Nasser’s mind, the two events became conflated as part of a neocolonial conspiracy to destroy his regime and reassert Western control over the entire Arab world.

Calls on Washington by the Egyptians for arms had gone unanswered and Nasser – contemplating what had previously been unthinkable – turned to the Soviets. To Nasser’s surprise, the Russians responded promptly and positively and also indicated a willingness to help Egypt with industrial projects.

Alarmed by this, the Eisenhower administration employed intimidation tactics, financial pressure and the threat of regional encirclement in a bid to get Nasser to break off this relationship, but it instead drove Egypt’s leader to build closer ties with the Soviet bloc.

The arms deal solidified Nasser’s popularity in Egypt, in the Arab neighbourhood and throughout the decolonised world, elevating him to the status of an international political icon.

"Eisenhower officials now saw Egypt as the rising power in Arab politics and Nasser as a tough and disruptive actor to be reckoned with," explains Professor Gerges. "Rather than confronting the Egyptian leader, they decided to co-opt him and try to buy him off."

In December 1955, the United States, together with Britain and the World Bank, offered nearly 70 million US dollars in aid to Egypt to help in the construction of the Aswan Dam on the Nile River. This massive development project aimed to contain the cycle of floods and droughts that had caused devastation to Egypt for millennia.

This was an extremely attractive offer. The Free Officers were keen to build the dam with Western technical aid as a way to reaffirm that Cairo was neither taking sides in the Cold War nor depending on Russia for aid.

However, the aid was predicated by the Eisenhower administration on Nasser signing a peace treaty with Israel and joining America’s global struggle against the Soviet Union.

Nasser rejected these conditions because they constrained his freedom to act regionally and internationally while letting Washington dictate terms that threatened Egyptian sovereignty.

Bilateral peace with Israel would equal political suicide and probably literal death – Nasser had already survived one assassination attempt.

Nasser strained his relations with the US further by recognising Communist China in May 1956 as a way to circumvent any possible agreement by the United States and Soviet Union to deny him arms.

In response, the US rescinded the Western aid package to build the Aswan Dam. Nasser, needing to protect the credibility of his regime, turned to the Russians and secured aid for the Aswan Dam at two per cent interest.

It is not too late to embrace the countries and peoples of the Middle East as equals and respect their choices and aspirations and open the path to productive collaboration.

America’s role in the Suez Crisis

In order to pay this loan back, Nasser could see only one way forward and that was to nationalise the Suez Canal Company, and thereby gain access to the toll revenue ships paid to use it.

He did so on 26 July 1956 – a historical step with an impact on the region that was comparable to Mossadegh’s nationalisation of the oil industry in 1953.

The Suez Canal is one of the most strategic waterways on the planet. It is the sole sea route for goods travelling from the east to the west, and vice versa, avoiding an expensive and time-consuming detour around Africa that adds 5,000 nautical miles to the journey.

The consequences of nationalising the Suez Canal were dire, with Britain, France and Israel invading Egypt with the aim of recovering control of the vital maritime trade link. The crisis almost escalated into a nuclear standoff between the two rival superpowers, but the forces of the three nations withdrew after facing threats from Russia and the US.

"The Eisenhower administration may have opposed the invasion, but it still contributed to the crisis," says Professor Gerges. "By trying to weaken Nasser by withdrawing the US offer to finance the Aswan Dam, Eisenhower set the stage for Nasser to nationalise the canal. If that hadn’t have happened, the Suez Crisis might never have taken place."

Considering Nasser a source of regional instability, Washington boosted his regional rivals. At a joint session of Congress on 5 January 1957, Eisenhower proposed a resolution that greenlit authorisation for the president to intervene militarily if any communist-controlled regime attacked any country in the Middle East or beyond.

The "Eisenhower Doctrine" achieved its aim of sowing divisions within Arab ranks, triggering a fierce Arab Cold War. States and societies were ravaged by geopolitical rivalries while inter-Arab competition undermined trust and the prospect of fruitful cooperation and trade.

Conservative monarchies were propped up by the US in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya and Tunisia. Thanks to Eisenhower, the Saudis were put in the lead because he believed that King Saud, the custodian of the Two Holy Mosques in Islam, could represent a spiritual counterweight to dampen Nasser’s charisma.

Why did the US fund Islamist groups?

The US decision to ally with Saudi's pan-Islamism and other Islamist groups against semi-secular nationalists and "godless communists" characterised its foreign policy from the late 1950s until the end of the Cold War in 1989. America’s partnership with the Afghan mujahideen against the Soviet invaders in the 1980s was not the exception but the result of a long-term strategy.

Billions of US dollars were pumped into pan-Islamist groups, dramatically altering the social and geopolitical balance of power in the region and beyond. Pan-Islamism of Al-Qaeda's variety climbed on the shoulders of America's informal empire, Gerges argues.

The Eisenhower Doctrine targeted first and foremost Nasser’s Arab nationalist project, which the United States viewed as a threat to its vital economic national interests in the region. The result was a toxic inter-Arab rivalry whose aftershocks still reverberate across the region and around the world today.

Egypt and Iran, possessing vast human resources and undertaking early modernisation efforts, could have inspired other regional countries, leading the way in establishing the rule of law, state institutions and productive industrialisation. Instead, they became more militarised and despotic.

The devastating effects were not felt only in the region. US support for Islamic-leaning groups and states in the Middle East served to create a pool of young, marginalised, jobless and angry men ripe for the picking by extremist organisations. All this unfolded against the backdrop of socioeconomic inequalities that were exacerbated by geostrategic rivalries. These were among the noxious roots of deadly terrorist attacks by militant groups in the United States decades later.

"Local actors bear a great deal of responsibility for the current crises in the region," says Professor Gerges. "But we must have a clear-eyed understanding that Anglo-American covert and overt and military interventions in the internal affairs of the Middle East strengthened and reinforced its worst sociopolitical trends.

America's imperial ambitions and actions from the early 1950s to the present "radically altered the trajectory of politics and development in the region," he continues.

"It is not too late to embrace the countries and peoples of the Middle East as equals and respect their choices and aspirations for self-determination, particularly the Palestinians who are struggling to end the Israeli occupation of their lands and have a state of their own," Professor Gerges concludes.

Professor Fawaz Gerges was speaking to Sue Windebank, Senior Media Relations Manager at LSE.

Image: Mohammad Mosaddeq and Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Download a PDF version of this article