The hidden production line behind AI

Contents

Discussions about AI and technology innovation, the language we use to describe data existing "in the cloud", ignore the physical infrastructure underpinning the development of seemingly intangible products, explains Professor Bingchun Meng, Department of Media and Communications at LSE.

In May 2021, Apple Inc. started the operation of its first Chinese data centre for the storage of all the user data originated in China, which was jointly built by Apple and Guizhou-Cloud Big Data (GCBD) in the southwestern city of Guiyang in the Guizhou province. Guizhou has often been ranked near the bottom of China’s 31 administrative regions and provinces in terms of gross domestic product (GDP). Developing data industries in Guizhou is part of a government-led long-term plan aiming for economic growth.

In July 2017, the Chinese State Council set out its ambition to position China by 2030 as the world’s preeminent expert on both research into and applications of artificial intelligence. In a recent book chapter, Professor Meng notes that Chinese AI companies have been very successful at raising funds from both domestic and overseas investors, resulting in increasing numbers of so-called "unicorns" (privately held start-ups with a valuation of over $1 billion). A recent sensational example is SenseTime, a Chinese company specialising in AI and facial recognition. SenseTime was able to raise $1.2 billion in the first six months of 2018, and is now valued at more than $6.2 billion.

As Professor Meng observes, "a seemingly productive alliance is shaping up between venture capitalists, technology companies and the Chinese government, inscribing layer upon layer of significance onto AI as the key technology of the future."

The physical space for data centres and the abundance of cheap energy supply are some of the hidden material requirements of the shiny end products we think of as ‘‘AI’’ that Professor Meng wants to draw attention to.

Why has Guizhou become a big-data hub

Cloud computing, networked machines and artificial intelligence all require the storing and analysing of huge amounts of data. Surrounded by mountains and forests, making it unsuitable for developing agriculture in the past, Guizhou’s plentiful supply of hydropower and wind energy and its cool "Nordic" climate have made it an ideal location for large-scale data centres that benefit from cheap electricity and natural cooling environments. Since 2013, the provincial government in Guizhou has made data and cloud computing the strategic priority for economic growth and development.

GCBD was set up in 2014 as the flagship enterprise, first to aggregate and manage data for delivering e-government services, before evolving into a platform for coordinating data trading and cloud computing activities at the provincial level. Major technology companies, such as Foxconn, Huawei, Tencent, Intel, Microsoft and Alibaba, have all set up data and computing centres in Guizhou.

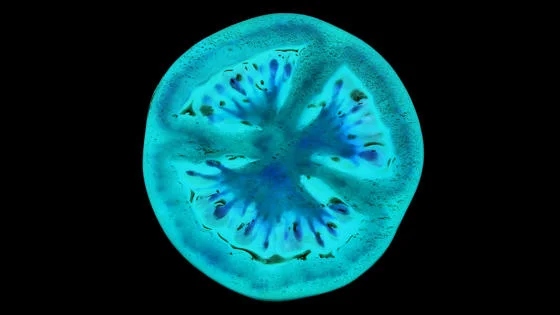

The Chinese tech giant Tencent’s data centre design was inspired by mountain caves. Covering 470,000 square metres, it accommodates 300,000 servers, one sixth of which sit inside its five tunnel caves.

The physical space for data centres and the abundance of cheap energy supply are some of the hidden material requirements of the shiny end products we think of as ‘‘AI’’ that Professor Meng wants to draw attention to.

"I use the concept of social imaginaries [the set of values, institutions, laws, and symbols through which people imagine their social whole]. And if we probe into some of the mainstream social imaginaries about AI, there seems to be this fantasy about the ‘cloud’ – it’s clean, it’s ethereal, and it’s somewhere out there doing wonderful things. But what is visible to the general public about AI is really the tip of the iceberg. Actually there’s a whole production line starting from lower-level data processing jobs, a materiality to AI that remains largely hidden."

If we really want to compare the sustainability and viability of AI-related industries, or data industries, in [USA and China], we probably want to look at a longer value chain and production line. It’s there that you will find that China actually has some advantage.

The production line that sustains AI superpowers

Professor Meng highlights the importance of the huge material infrastructure and human labour that is overlooked in general discourse about AI. Discussions about the rivalry between the US and China for AI supremacy, for example, often focus on the end products.

"Think about the shock wave that DeepSeek sent through the world when it released its chatbot. Everyone was focusing on the (in)effectiveness of US sanctions against China on cutting-edge semiconductor chips. But actually, if we really want to compare the sustainability and viability of AI-related industries, or data industries, in these two countries, we probably want to look at a longer value chain and production line. It’s there that you will find that China actually has some advantage."

In Professor Meng’s research in Guizhou, she observed the substantial effort and resources that were being put into the less visible parts of the AI production line. "Big Data in Guizhou was conceived from the beginning as a public utility, heavily subsidised by the state."

Local government officials are aware that they cannot compete in attracting top talents and innovating at the commercial application end, "but they also know that they have a place to occupy on this value chain and they have their own advantage ... they are necessary to sustain the innovation in Shenzhen and Beijing."

The Guizhou provincial government has been actively incentivising companies like Huawei and Tencent to build their infrastructure in the province, with cheap leases on land, for example, but also access to cheap labour.

The human workers training AI algorithms

"There is a lot of discussion about automation replacing human labour, but there isn’t nearly enough discussion about how much human labour will need to be invested in the first place to train AI, to train the algorithms."

Since 2021, Guiyang and the Guian New Area (a 1,795 sq km suburb created in 2014 to attract major technology companies) have created over 150,000 new urban jobs annually The main site where Professor Meng and her team did their fieldwork was a vocational school, Shenghua Vocational College, affiliated with a data processing company, which trains students in the skills needed to work in data processing centres. Around 200 students in each cohort go on to do a placement in the affiliated company.

These students don’t have the grades to attend university, and the school is heavily subsidised offering significant financial support, so students Professor Meng spoke to were grateful for the opportunity to build these skills and enter the workforce. "They also felt there is some kind of ‘aura’ associated with the industry – of working in what they call a data processing workshop, rather than on an assembly line."

To sustain the development of AI, it requires a kind of co-evolution of human labour and technology.

The future of work and Big Data in Guizhou

Although the training opportunity is welcomed, these jobs are low-paid and very vulnerable in a rapidly changing industry.

"Those workers we had focus group discussions with [from the affiliated data processing company], they are eventually working towards having themselves replaced."

Ten years ago, many workers started with the simple task of training algorithms for autonomous driving. This was very monotonous work looking at hundreds of pictures of traffic scenarios and drawing frames around traffic lights, vehicles, pedestrians crossing the street, etc. This type of work no longer exists as that training is complete, and this is a tension that Professor Meng sensed in the school and amongst local officials. "Everything changes so fast in this sector there is an anxiety and constant need to upskill. That’s even reflected in the changing of the company name from data labelling to data processing."

But it’s too simplistic to say that these jobs will completely disappear. It is clear that in the deployment of AI human interaction will still be needed, and Professor Meng sees a continuing demand also at the development end. "To sustain the development of AI, it requires a kind of co-evolution of human labour and technology." But, she acknowledges, "that is often a challenge for the labour force that is on the lower end of this value chain."

The risk of investment in a rapidly changing technology was also apparent to the government officials who spoke with Professor Meng. The original vision of Guizhou processing all the data from the wealthier coastal cities is collapsing as those coastal areas start to develop their own data centres. "The province is also very anxious about how they can co-evolve with the technology, and how to move up the value chain."

Understanding the material costs of delivering AI

AI is now hailed by national governments around the world as the key sector for future economic growth, with investment in AI, machine learning and robotic process automation technology set to reach $232 billion this year.

But the public understanding of how AI is built remains limited, with a disconnect between the digital end product and the physical infrastructure and labour that lies behind it. Professor Meng believes that a better understanding of these hidden material costs and requirements is essential when discussing the role of AI in our future.

Professor Bingchun Meng was speaking to Louise Jones, Head of Research Communications and Engagement at LSE.

AI, technology and society special edition

At LSE our researchers are using technology’s revolutionary power to understand our world better, looking at AI and technology’s potential to do good, and limiting its potential to do harm.

Browse upcoming events, short films, articles and blogs on AI, technology and society on our dedicated hub.

Join us on campus or online wherever you are in the world for LSE Festival: Visions of the Future, a week of special events 16-21 June 2025, free and open to all.

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a world-leading university, specialising in social sciences and named University of the Year by the Good University Guide 2025. Based in the heart of London, we are a global community of people and ideas that transform the world.