Why online tabloids are better at predicting the public’s political mood than broadsheets

Contents

Where do you go to get your political news? Many will argue that broadsheets are the best source for factual coverage and analysis, relegating tabloids – particularly online ones – to the role of guilty pleasure. A place to read about lightweight or celebrity news, but certainly not a trustworthy political source.

A new book by Dr Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer, Visiting Fellow in the Department of Media and Communications at LSE, however, suggests it would be a mistake to dismiss the political power of these sites. She argues that online tabloids have become vital sources of political news for the public, and sets out how they have managed to accomplish this.

While their mix of celebrity and politics, sensationalist copy and strong (some might say biased) political opinions are often given as reasons to dismiss online tabloids as political lightweights, she argues it is in fact exactly these attributes that have enabled them to become vital sources of political news for the public.

Looking at the way the news was presented … it appeared like they had some different – and in retrospect more accurate – insights into the political mood of the public.

Online tabloids align with the public mood

"Online tabloids can be awful places, but everyone reads them anyway, because they’re awful. But also because they can be very funny, and sometimes they have a point," Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer explains.

"They’re also very accessible – that's their magic. It happens in the headlines, in the editing. It definitely happens in the photos. They have an emotional style of writing that tends to stick, and this all combines to give them an emotional component – not just what we should think about something, but how we should feel about it."

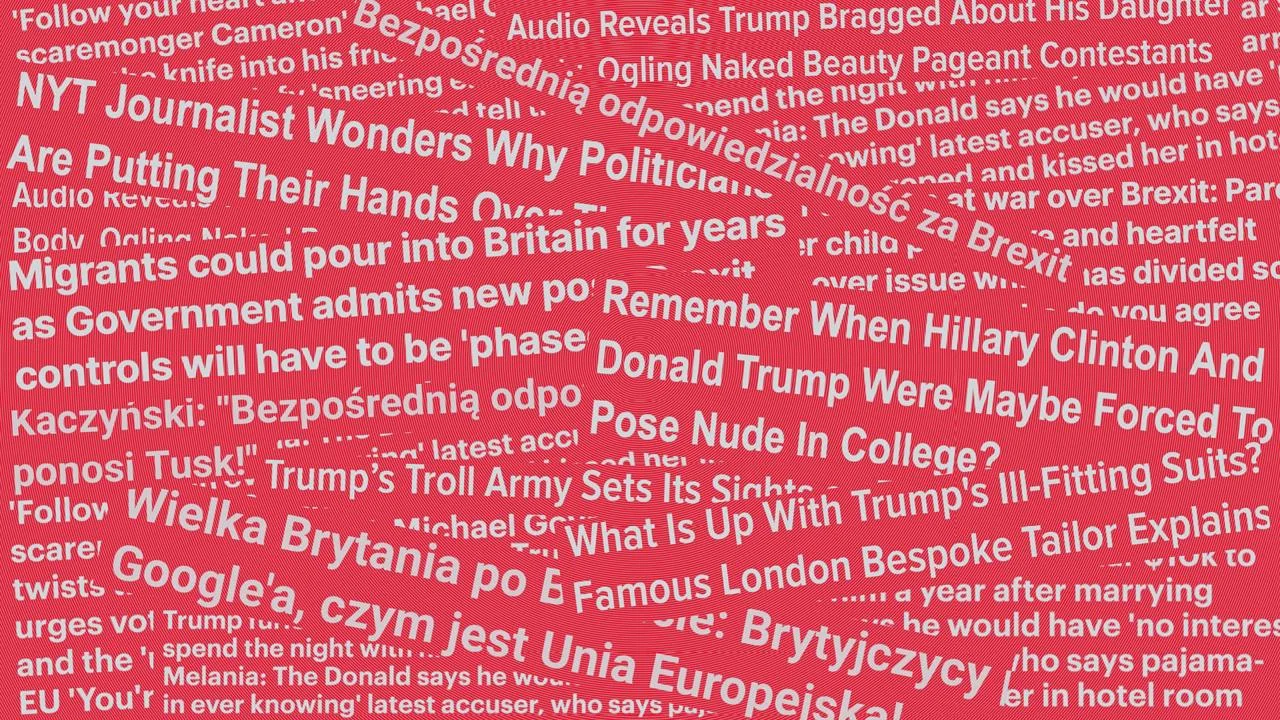

Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer's interest in the political coverage of online tabloids was sparked following the Polish election of 2015 and 2016’s US election and Brexit referendum. Unlike each country’s broadsheets, which misread the public mood and failed to predict the outcomes, the online tabloids in each country were more closely aligned with the shift in public mood that led to each result.

"Looking at the way the news was presented, and how their commentators were discussing the topic, it appeared like online tabloids had some different – and in retrospect more accurate – insights into the political mood of the public. So I decided to take a deeper look at what was going on," she says.

To explore what was happening, Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer analysed over 2,000 articles of campaign coverage across all the top tabloids of each country – Pudelek in Poland, the Mail Online for the UK, and the now closed Gawker in the US – in the two months leading up to each vote, as well as their most upvoted comments. She also conducted 20 interviews with political journalists working for all three sites.

Celebrity and politics are extremely entwined in tabloid coverage. This influences how politicians are shown –- they are portrayed as different versions of celebrities.

Online tabloids have power and reach

Understanding why these sites’ political coverage was so closely aligned with the public’s mood is important, she explains, because despite common perceptions that they speak to, and for, the non-elite and underrepresented, all have significant readership – the Mail Online attracting almost 25 million unique visitors per month, Gawker, almost 14.5 million before it closed in August 2016, and Pudelek, around 6.6 million unique visitors.

Despite these tabloids coming from different nations, and having different styles (Pudelek journalists, for example, are anonymous whereas Mail Online journalists have bylines), Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer found more similarities than differences between each publication.

Alongside their more accessible style of writing, imagery and ability to be more daring in their presentation of events through strong headlines and copy than broadsheets, she identifies their focus on celebrity as one key reason they have been able to pull their readers along with them. It is no secret that online tabloids enjoy celebrity news. However Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer was surprised by how closely celebrity and political content are presented on these sites.

"When you look at just the political coverage, it’s really interesting how saturated it is with the kind of showbiz and lifestyle type of celebrities that tabloids are known to feature. There are so many celebrities mentioned in my book – Kim Kardashian, Paris Hilton, Howard Stern. Celebrity and politics are extremely entwined in tabloid coverage. This influences how politicians are shown – they are portrayed as different versions of celebrities," she says.

Journalists from all three outlets told me that their outlets were reactive to their audiences.

The importance of the comment section

One other key asset that online tabloids utilise to their benefit is comment sections below each article. These have been particularly valuable in enabling them to align themselves with the general zeitgeist, the data shows. Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer's analysis of the most upvoted comments accompanying each article reveals a strong link between the comments left and the angles taken by the paper in follow-up or similar news stories.

"The comment sections in these online tabloids are almost seamless extensions of the articles themselves, so I also looked at their use of the commentary responses to understand the relationship between the news coverage," Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer explains.

Each tabloid has its own way of managing its comments section – on Gawker you could find journalists engaging in conversation with readers, while journalists writing for Mail Online wouldn’t visibly engage but would make corrections or shift their emotional stance in subsequent coverage if readers were strongly opposed to their initial angle. All, however, took these sections seriously.

"Online tabloids rely on emotions and so they have very openly laid out moral stances. Journalists from all three outlets told me that their outlets were reactive to their audiences," she says.

While all those she interviewed said they read the comments, some would go further and interact with certain comments. "At Gawker, commenters would correct their mistakes openly, or respond to another reader’s comment. Sometimes they would joke together."

"Also, some of the more upvoted commentators were given moderator powers so could also moderate comments. This had the impact of flattening the conversation – it became less top-down and almost more democratic."

Alongside the tabloids’ common use of sensationalist copy and opinionated articles – all ways to excite and engage readers – comes the risk of potentially alienating that readership base if coverage strays too far from what they consider acceptable. Online tabloids have a keen awareness of this risk, finds Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer. As a result, if an angle elicited a particularly strong negative reaction in the comments, the paper would shift its perspective, with subsequent news stories aligning more closely with the most upvoted comments from its readers.

"My analysis finds that if the audience reactions in the comments are not the reaction that is in line with what the writers are proposing, then they might switch, and future articles will take a different stance that is more in tune with the comments they have received previously," she explains.

For this reason, the comments section is not just a place to encourage readers to interact, but has also become a useful way for editors to judge where best to pitch future coverage, enabling them to understand what angles are working, but what might risk alienating their base.

"When I started researching this, I saw that many people were telling each other that they were actually going to these sites for the comments, not just for the articles," Dr Chmielewska-Szlajfer observes. With these sections providing valuable data on each site’s readership, it is not simply the public who are poring over these sections.

With no sign that these tabloids are going to lose popularity any time soon, perhaps it is time to also consider online tabloids, alongside their more serious broadsheet colleagues, as spaces of political authority, she concludes.

Dr Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer was speaking to Jess Winterstein, Deputy Head of Media Relations at LSE.

Download a PDF version of this article

2024 is a year of elections. What happens when the world goes to the polls?

- Read more articles from this global politics special edition of the LSE Research for the World online magazine.

- Explore our dedicated hub showcasing LSE research and social science commentary on key debates and emerging themes in global politics.

- Join us for the LSE Festival: Power and Politics, a week of events from 10 to 15 June 2024. Dr Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer's work features in the LSE Festival Displays of Power exhibition.