Are girls being designed out of public spaces?

Contents

When asked during a discussion session what public spaces there were for girls, one 17-year-old paused before answering. "There's nowhere for girls. There's literally not a specific place for girls. There's places where we go, but no spaces for us." Another chimed in ironically, stating "a women’s toilet?" Their answers reveal a disconnect between girls and young women and the areas in which they live. These responses have emerged from our research into girls and young women’s sense of inclusion in public spaces in the UK and are echoed by many across the country.

In 2022, seeing a need for public space provisioning to better engage girls and young women, Dr Julia King and Olivia Theocharides-Feldman of LSE Cities and the advocacy group Make Space for Girls began a "researcher-in-residence" style peer research programme.

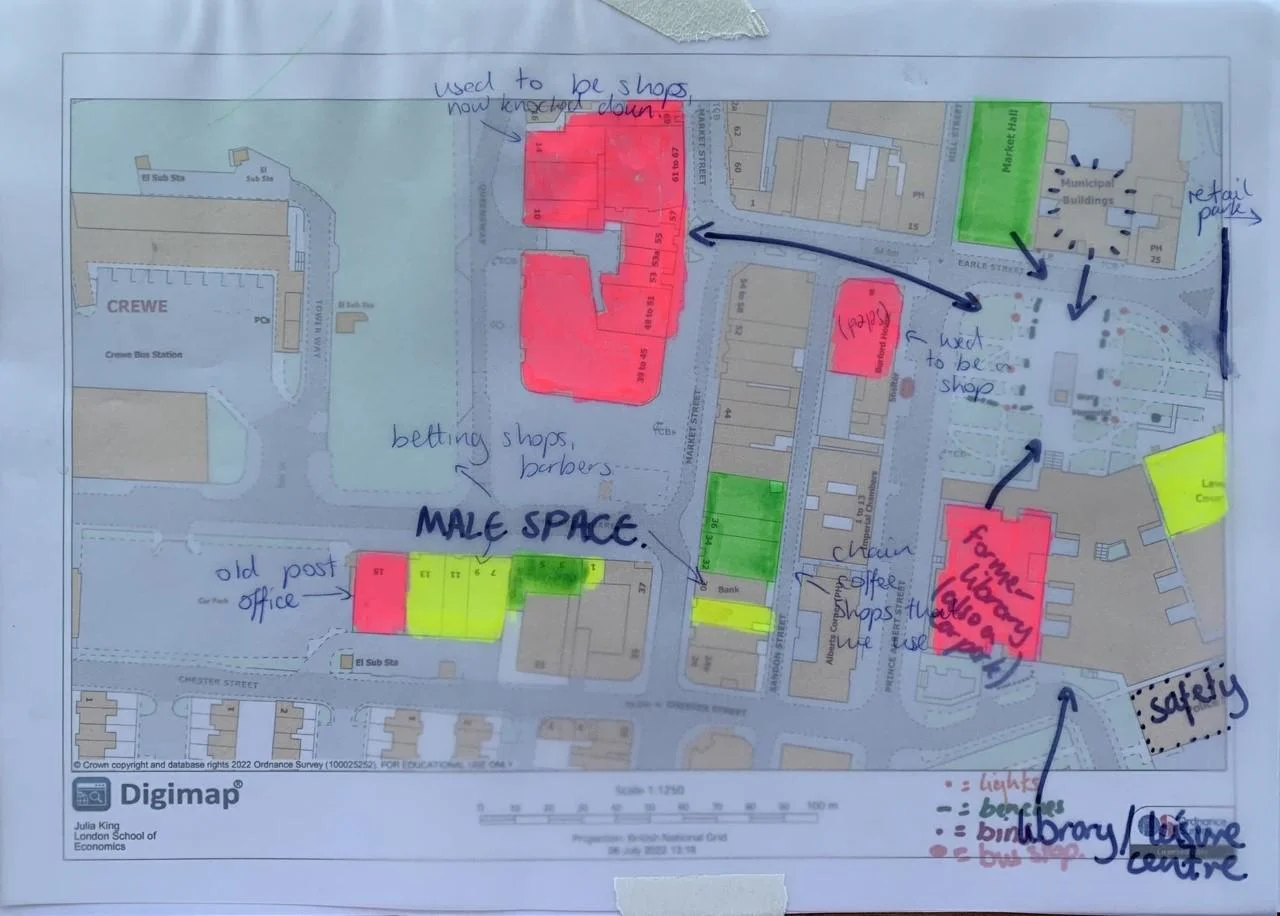

The programme ran as a seven-week paid learning and working experience with nine 17-21 year old individuals who identified as girls and young women. It put forward a novel way of conducting peer research: Zoom and Miro (an online whiteboard) were used to run weekly discussion sessions, upload lectures, podcasts, and readings; the researchers-in-residence used Instagram to chronicle their self-led weekly site visits, and two in-person guided visits and mapping exercises were run with the researchers-in-residence in their local areas.

Through valuing their lived experience, and a curriculum which taught them spatial theory and engaged them in social scientific research and architectural methods, the researchers took on the research question "have girls been designed out of public space?"

While they did use local public spaces, [the researchers-in-residence] all felt these were exclusionary... Public spaces were zones of judgement.

The girls were selected from Crewe and Trowbridge, two areas in England that have been allocated significant funding from central government (through Levelling Up and Future High Streets funds) to transform their public spaces.

As part of the project the researchers-in-residence were connected with local stakeholders that were effecting change: an architect tasked with revitalising the town centre in Trowbridge, and a planner tending to parks and a new parks strategy in Crewe. Working together, the girls ultimately suggested how to better design public spaces for girls and young women.

Public spaces are overwhelmingly designed for males and adults

Public spaces are crucial for young women’s physical and mental development. Public space use increases physical activity and its associated benefits, and offers young women respite from home life, while providing them with opportunities to socialise, interact with peers and develop their independence.

In planning for public space, over 89 per cent of youths in England aged 16-18 have never been asked about their local areas; and in the UK, women comprise only 14 per cent of the built environment workforce. This has resulted in spaces that favour certain demographics over others.

Through their discussion, reflections and self-led site observations, the researchers-in-residence quickly evidenced that while they did use local public spaces, they all felt these were exclusionary. Public spaces were not safe or fun enough. Public spaces were zones of judgement: in children’s playgrounds and retail spaces they felt targeted by adult users, security guards, and CCTV. High streets and retail centres were laden with disinteresting and unaffordable retail. They felt that they could not travel to spaces safely, reliably and cheaply. Women’s toilets were too sparse, often not free and always had queues and overflowing sanitary bins. There were insufficient amenities like water bottle refill stations and inadequate spaces to just hangout with friends.

While youth allocation money is meant to target this group of girls, investments into facilities are almost singularly funnelled towards … areas which are used practically entirely by boys and young men.

During the guided mapping exercises in their local areas, it became evident that while the researchers-in residence were unable to recognise spaces for them, they were, however, quick to identify the "male only" and "adult only" spaces in their local areas.

Basketball courts, football pitches, skateparks, as well as dark alleyways, betting shops and pubs were, the researchers-in-residence felt, for men and boys; retail spaces like shopping centres and high streets were for adults. These areas comprised the no-go zones of their personal and embodied local maps. Such spaces were avoided for many reasons: in some cases because their design felt unsafe, or other users (male peers and adults) made them feel intimidated; in others because they were simply unappealing or inaccessible.

For girls and young women trying to find their place in public space, the issue is often a twofold one: it is both a gendered and an aged dilemma. Girls and young women are too old to use children’s spaces, like playgrounds, and too young to use adult ones, like unaffordable retail. Simultaneously, while youth allocation money is meant to target this group of girls, investments into facilities are almost singularly funnelled towards skate parks, BMX tracks, and MUGAs (enclosed football pitches, basketball courts) – areas which are used practically entirely by boys and young men.

When girls and young women try to design themselves into places, they end up designing a lot of other groups in as well, like those with disabilities and boys who simply don’t like football.

How can young women carve a place for themselves and what would that look like?

Reflecting on their experiences, and having been taught through the curriculum about gender sensitive planning and precedence in different global case studies (in Vienna for example), the researchers-in-residence wanted public spaces that were accessible, welcoming, clean, safe, free, fun, playful, diverse, green, social, relaxing, enjoyable, and which could provide access to basic needs. They wanted to feel included, welcome, safe, unjudged, accepted, and happy.

All girls expressed that for public spaces to be enjoyable they first had to feel safe with good lighting and wide pavements for example. But safety was not enough; spaces should also be fun and judgement free. They wanted transport to and from public spaces to be affordable, accessible and safe.

All the girls valued green open space to "relax". But they wanted youth facilitates in those spaces to extend beyond male dominated ones and into swings, trampolines, hangout spots like sheltered benches facing one another, or games areas where rules could be improvised. In high streets and retail centres, girls valued social spaces with affordable businesses that targeted their demographic; where they could sit for free, or enjoy a "cheap" coffee and a shopping day with friends.

Crucially, they wanted to be heard; they felt that the users of a public space should participate in its design and that those voices should be diversified.

A selection of images taken during the project.

What have the young researchers taught us?

The input of our researchers-in-residence has been eye-opening and insightful. We learned that girls and young women do feel designed out of public spaces. We learned that rather than having planners guess, girls and young women can easily articulate their unmet wants and needs. We also learned that when girls and young women try to design themselves into places, they end up designing a lot of other groups in as well, like those with disabilities and boys who simply don’t like football. Mainly, it was found that for girls and young women to be included in public space they need to be given the tools to research their own experiences, have a voice in planning and inform design.

But the project has not only been about advocacy; it has also explored novel methodologies of undertaking spatial research and the researchers-in-residence’s findings have touched on areas currently unexplored by existing academic literature. For example, we have gleaned novel insights into the ways in which aspects like judgment, typically conceived of as interpersonal and social, are in fact also spatial. Indeed, a swing that is too narrow to fit a young woman’s hips does impart judgment on that person.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only drawn greater attention to how important it is to have just and inclusive public spaces but if girls and young women are missing from design, decision-making and planning processes, how can we ensure that spaces are truly inclusive for them? And how can and should research and academic institutions play their part?

This piece was written up by Olivia Theocharides-Feldman, Researcher at LSE Cities working on Making Space for Girls, a project led by Dr Julia King. The research discussed in this piece has been conducted by the researchers-in-residence in Crewe: Abbie Jones, Abigail Rose Lewis and Rowena Louise Jones; and in Trowbridge: Alice Hanney, Havin Celik, Lauren Bee, Lillie-Anna Wing, Isabella Thomas, and Marina Joliffe.

Download a PDF version of this article