A budget for (green) growth? Unfortunately, not yet

In light of the climate crisis, the energy and cost-of-living crises, and longstanding productivity problems that urgently need to be addressed, this budget was a key moment for the UK Government to make progress providing the building blocks for a productive, sustainable and resilient future. Esin Serin and Anna Valero ask: to what extent has the Spring Budget taken us in the right direction?

In the run up to the Spring Budget, many had been expecting a budget for more “normal” times (at least compared to last Autumn) with some optimism around the fiscal headroom which would allow the Chancellor to be more generous in certain areas. Many such areas were pre-announced, and welcome – from more free childcare allowing women to stay in work when they wish to do so, to high-tech Investment Zones with the potential for generating regional growth, and support for nuclear and carbon capture usage and storage (CCUS) – both of which are important for the UK’s journey to net zero.

The Chancellor made clear that this budget was about growth, and began with some very upbeat messaging about the UK’s economic performance. But the reality is that we have become a “Stagnation Nation”, in urgent need of a new economic strategy in times that are far from normal.

Investment for growth

A key determinant of the UK’s underperformance on productivity has been weak business investment. As a share of GDP, this has been weaker (at under 10 per cent) than in our main comparator countries France, Germany and the US (where it is over 12 per cent on average), and has suffered in particular since the Brexit vote.

The corporate tax environment matters for investment decisions, and the announced full expensing of capital expenditure for three years – in light of the increase in the main rate of corporate tax and end of the super deduction this April – is likely to boost investment relative to the counterfactual. The OBR expects business investment to be around 3 per cent higher while the scheme is in place, but it makes clear that such a scheme would need to be permanent in order to do more than simply bring forward investment from later years. Clearly more of a boost is needed if we are to increase our investment rate to match other advanced economies. A more stable and less distortionary corporate tax system would help to move the UK onto a higher investment, higher growth path.

Investing in innovation is key for a knowledge economy like the UK, and even with recent ONS restatements, the UK still lags behind some of its main comparators when comparing R&D as a share of GDP. The Autumn Statement saw a rebalancing of support in the R&D tax credit scheme towards larger firms, which created risks for innovative smaller businesses and the broader spillovers that tend to flow from their activities. In response, enhanced support for loss-making, R&D intensive smaller firms was provided in the current budget. While this is a positive for some in the current context (R&D in smaller, credit-constrained firms tends to suffer in a downturn), it won’t help innovative firms that either don’t meet the threshold (40 per cent of their costs on R&D) or those that are making a profit. The Government has been consulting on simplifying R&D tax incentives, but these frequent piecemeal changes add complexity and undermine confidence for companies accessing the scheme.

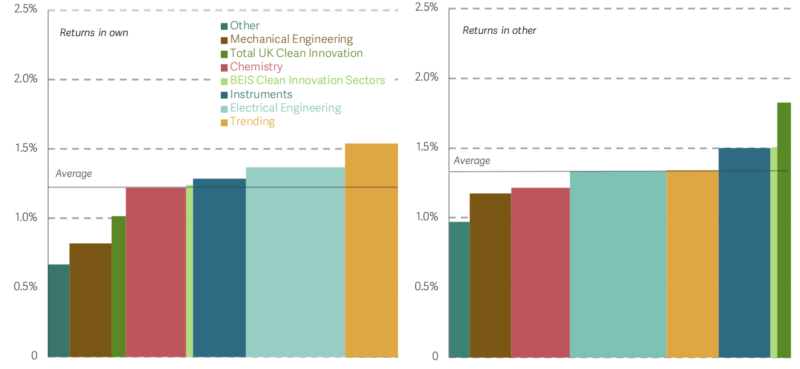

Addressing largescale disparities in investment will be needed for both levelling up and improving aggregate growth for the UK. The previously announced refocusing of Investment Zones around universities or research institutes, combined with various measures to increase local powers for regional development, are promising. Indeed, universities have great potential to contribute to regional growth, particularly when their specialisms are close to local industry, but it will be important to avoid deadweight and displacement that tend to accompany area-based tax incentives. And we shouldn’t overlook the barriers to growth faced by our already strong clusters within the so-called “Golden Triangle” – which not only generate local growth but also innovation spillovers to the rest of the country (particularly in the case of clean tech, as shown in Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Returns to public investments in innovation taking place in “golden triangle” regions, retained in those regions (left panel) and felt in the rest of the country (right panel)

Source: Chart taken from Curran B et al. (2022) Growing clean: Identifying and investing in sustainable growth opportunities across the UK. London: The Resolution Foundation. Analysis builds on Martin R and Verhoeven D (2022) Knowledge spillovers from clean and emerging technologies in the UK, CEP Discussion paper 1834.

Some mention of skills funding was made in the context of Investment Zones, but otherwise this budget said little about broader education and skills policies which are key for achieving growth, reducing inequalities and addressing bottlenecks in key growth areas (including net zero).

The direction of growth: investment for net zero, resilience and sustainability

Actions to increase the amount of business investment are crucial, but clearly the natureof that investment also matters – particularly when it comes to net zero, where government commitments and incentives are needed to overcome numerous market failures and deliver largescale investment at pace.

Since the US passed its landmark Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 with its $369 billion support for clean technologies, the global “green race” has become more heated than ever and, as the Skidmore Review pointed out, “we are now at a crunch point where the UK could get left behind”.

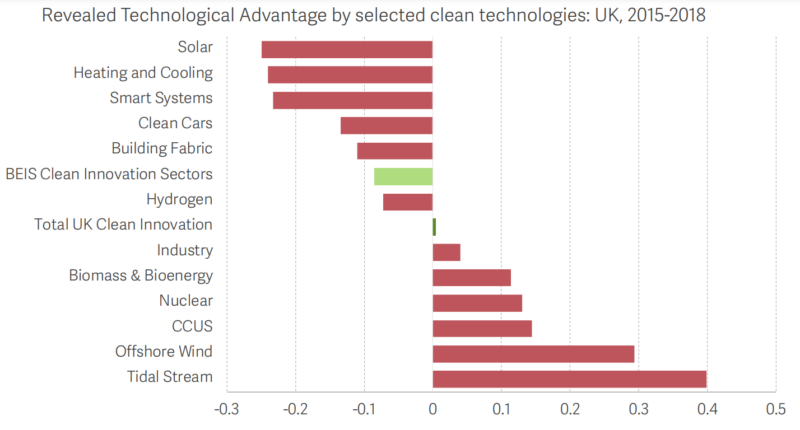

Currently the UK Government spends a smaller share of its GDP on net zero compared to many developed economies with comparable climate ambitions, including the US, Germany and France. The UK cannot compete in terms of the scale of support, but must now respond with a clear and targeted strategy for areas where it has or can build comparative advantage, or where energy security demands it. The prioritisation of CCUS and small modular reactors (SMRs) in the budget might be a sign that the Government is deciding what it wants to be good at. Indeed, these are both areas where the UK appears to have some innovative specialisms, as Figure 2 below shows.

Figure 2. Revealed technological advantage by selected clean technologies: UK, 2015-2018

Source: Analysis of PATSTAT 2021, Autumn edition. Chart taken from Curran B et al. (2022) Growing clean: Identifying and investing in sustainable growth opportunities across the UK. London: The Resolution Foundation.

But both of these technologies are years away from being able to make a substantial contribution to decarbonising UK energy. Meanwhile the clock is ticking on the 2035 target for a fully decarbonised power system, a target that is looking increasingly challenging in the absence of a long-term plan to accelerate the delivery of readily available and cost-effective renewable technologies. Overcoming grid constraints and restoring investor confidence (especially for onshore wind and solar) should be a priority.

As other countries are demonstrating, there is potential to do more in the tax system to provide enhanced incentives for net zero-aligned investments in fixed capital assets or R&D. And there is scope for better designing levies on electricity generators to incentivise investment; the Electricity Generator Levy acts as a windfall tax on renewable companies but without offering the kind of investment allowances available under the Energy Profits Levy serving the equivalent function in the oil and gas sector. While taxing excess profits is sensible in both sectors, the current approach creates a perverse signal that may hurt investment in renewable generation.

Turning to households, the extension of the Energy Price Guarantee for an additional three months was both welcome and inevitable, but energy prices remain volatile and the Government must step up efforts to decarbonise homes, improving resilience and affordability in the future and meeting net zero commitments at the same time. The budget announced government plans to refresh the Control for Low Carbon Levies which would be positive for home decarbonisation if it means progress on rebalancing electricity and gas prices. However, the fact that the ‘up to £20 billion’ support for CCUS was not reflected in formal budget costings might suggest it will be levied on energy bills, which would entrench inequality especially at a time of existing hardship as low-income households spend a higher proportion of their income on energy bills.

The Chancellor made new funding for energy efficiency available from 2025 in the Autumn Budget, but what is needed is more than a headline figure, providing clarity on policy delivery starting today. Recent analysis has shown that around one-third of the funding supposed to be used to decarbonise homes between 2020 and 2025 remains unspent and action is needed to build public awareness, supply chain capacity and workforce skills. On transport, keeping fuel duty frozen yet again – rather than focusing on a long-overdue reform of transport taxes – again fails to strengthen the move away from petrol and diesel vehicles while also missing out on another term of much-needed government revenues.

Looking forward to “Green Day”

The measures announced in this budget are unlikely to move the dial on increasing business investment, delivering on net zero or capturing the opportunities for growth and improved resilience along the way. We look forward to further announcements from the UK Government as it updates its Net Zero Strategy (as ordered by the High Court) and responds to the Skidmore Review on what has been termed “Green Day” by the end of this month, for progress on delivery and the UK’s response to the Inflation Reduction Act.

This post is published in collaboration with the London School of Economics British Politics and Policy blog.