Just transition in the UK – how strong is the Net Zero Review on implementation?

Almost a year on from its interim report, Her Majesty’s Treasury last month published its Net Zero Review. In the intervening months, how much has the Treasury’s thinking developed on how to deliver a just transition to net-zero in the UK while capturing growth opportunities, asks Esin Serin.

Following the new commitments made at COP26, attention now turns to implementation. In the UK, the Government published its Net Zero Strategy ahead of COP, while delivering the Strategy in a just way – a pressing policy challenge – is the focus of the Treasury’s Net Zero Review.

In this follow-up piece to my response to the interim report for the Review, I evaluate the extent to which the Treasury has built on its earlier findings to develop a strong, actionable policy framework that fairly distributes the benefits and costs of the transition to net-zero – and where gaps still remain.

Clean growth potential

The Treasury emphasised the clean growth potential from net-zero in its interim report published one year ago. The final report builds on this rhetoric with an upfront recognition that “a successful and orderly transition for the economy could realise more benefits … than an economy based on fossil fuel consumption”. The Government has already outlined certain sector-specific policies in its Net Zero Strategy, designed to realise such benefits on the way to net-zero. The UK Infrastructure Bank – which will be a pivotal institution to crowd in private finance and bring forward net-zero-aligned infrastructure projects at scale, as I previously wrote – has also been launched since the interim report and has an explicit objective to support tackling climate change.

However, despite the interim report having set an objective to look at where the UK might have comparative advantage and consider how to maximise the economic benefits, the final report is only indicative on this point. It says the Government will start by looking at areas of existing strength and points to methodologies that could be employed to identify comparative advantage, such as the novel approach developed by Mealy and Teytelboym (2018).

The report does not go far enough here: it does not demonstrate an analytical framework or explain how the information acquired would feed into policy choices that need to be made for maximising economic benefits.

Identifying specific opportunities

There is already a substantial evidence base on the UK’s comparative advantages relevant for a sustainable growth path: for example, this economy-wide evaluation of the case for sustainable growth in the UK, and detailed assessments for specific sectors, including zero emission passenger vehicles and carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS). Our recent work has found that many CCUS-related products that the UK already exports competitively or could do so in the future are in the measuring, monitoring and verification (MMV) instrument category, and illustrates how this type of evidence could assist in developing targeted policies.

Such work provides scope to go beyond indicative statements of intention and provide firmer direction for public investments into specific areas that show the strongest potential to deliver net-zero along with other overarching government objectives. These include a resilient economic recovery from COVID-19, boosting productivity, investing in infrastructure, levelling up across the UK, and redefining the UK’s role in the world.

Distributional impacts

A just transition to net-zero requires both the opportunities and costs to be distributed fairly across society. The Net Zero Review highlights the Government’s intention to take a more nuanced look at household characteristics within each income decile and how impacts will vary between them, to design fair net-zero policies. This is a necessary and welcome intention but there is little detail on how it would work in practice, leaving the Review without any solid suggestion of how ‘distributional impacts’ will be mitigated.

When it comes to mitigating the distributional impacts of net-zero, wider changes to tax and welfare should not be ruled out. While the ‘polluter pays’ principle may offer an efficient way to drive decarbonisation, the Treasury acknowledges that a different approach may be justified for some groups, particularly for households at risk of fuel poverty. General taxation needs to be considered as a fairer and practical approach to recovering low-carbon policy costs.

Owen and Barret (2020) find that general taxation would offer a progressive way of funding low-carbon policy and would reduce costs for 65% of UK households compared with the current approach, where low-carbon policy costs are levied on energy bills.

Innovation for sustained growth

The Treasury’s discussion of the UK’s competitiveness in the green economy focuses heavily on its current comparative advantages. Innovation – despite being an enabler of future comparative advantage and therefore sustained growth – is discussed separately for the most part in the final report and primarily for its role to allow a low-cost transition. While reducing technology costs is one crucial objective of investing in innovation, making these investments strategically can bring other economic benefits into the future, including increased productivity and contributing to levelling up across the UK.

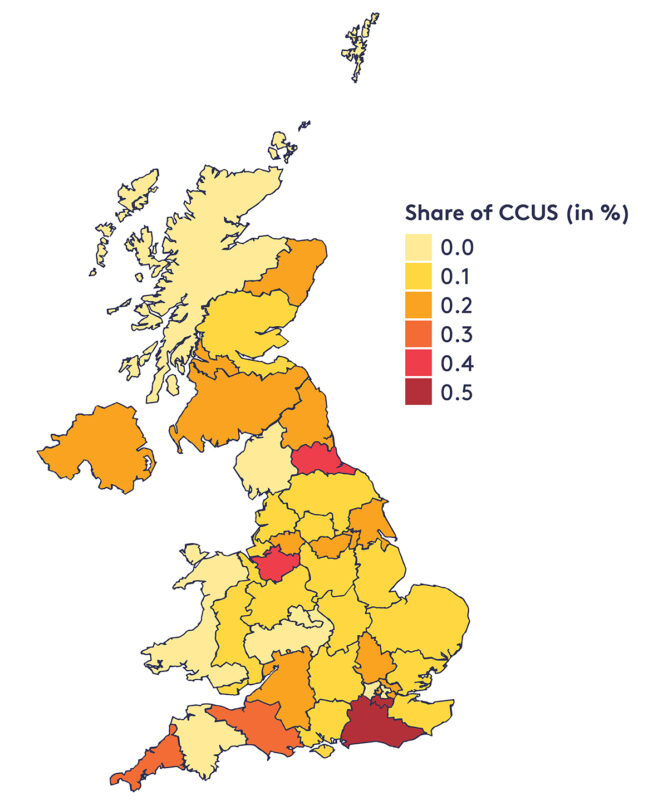

Our analysis has shown that CCUS can contribute towards levelling-up if support is directed strategically to address the unequal distribution of innovative performance across the country. We have seen that areas in the South East, as well as the industrial heartlands in the North East and North West of England, are strongly placed to act as CCUS R&D hubs (Figure 1).

Where potential for such wider economic benefits from net-zero-aligned investments is so strong, the Treasury’s ruling out borrowing on the grounds of intergenerational fairness appears counterproductive. There is a firm case for borrowing for productive investment in long-term assets to be distinguished from spending. The Treasury should therefore prioritise mitigating the worst impacts of climate change while we still can above all else, as we previously wrote, since an irreversibly warming planet would surely be the most unfair legacy to leave for future generations.

Figure 1. Share of CCUS innovation out of total innovation in the UK, 2000–15 (share of patents at NUTS2 regional level)

Source: Estimates by Serin et al. (2021), based on PATSTAT – 2018 Spring Edition

The Treasury articulates in the Review its intention to rely on the private sector “to lead the majority of the investment required” in innovation. However, as it also states, it will be the role of government policy to “create an environment that encourages concentrated innovation by firms”. Creating such an environment will come down to investing in innovation within a holistic package of investments for sustainable and inclusive growth – including in infrastructure, human, social and natural capital. Especially given the significant fiscal challenges discussed in the Review, the Treasury could have placed stronger emphasis on measures beyond direct public R&D spending to incentivise private sector investment in net-zero innovation, such as demand-side measures to create the ‘pull’ for innovative low-carbon products.

Investing in net-zero skills

The Treasury’s discussion on human capital in the final report is especially slim, despite education and skills being central to the ability of government to deliver many of its planned net-zero-aligned investments. Crucial work is ongoing as the Government works to embed and build on the recommendations of the Green Jobs Taskforce. However, this is an area that would have benefitted from stronger commitment to investment directly from the Treasury, including in programmes to re- or upskill the workforce in line with net-zero.

Against the backdrop of capacity bottlenecks that ultimately led to the Green Homes Grant scheme being pulled, closing the low-carbon skills gap is especially crucial across housing supply chains. For instance, the Government’s target to install 600,000 heat pumps per year by 2028 is estimated to require more than 30,000 new qualified installers within the next seven years.

Fiscal thinking evolves

An evaluation of the Review alongside the Net Zero Strategy suggests the Government is placing greater focus on taxation and regulation over subsidies, which historically have been the preferred option for driving decarbonisation. This choice could well be a better use of public money: research in the EU context suggests that carbon pricing is the most cost-effective policy instrument for reducing emissions while technology-specific subsidies to mature low-carbon technologies are unnecessarily costly to society. But successful implementation of an approach that is reliant on taxation and regulation is not without its challenges and requires political will and leadership sustained over the long term.

Framing carbon taxes in the final report as part of the wider, structural changes under net-zero is welcome. However, the detailed discussions that follow are not fully aligned with this thinking, especially where carbon tax revenues are presented as a tool to replace lost revenues from fossil fuel related taxes. While such analysis is necessary for an in-depth understanding of the fiscal implications of net-zero, the government narrative needs to remain nuanced throughout to emphasise carbon taxation first and foremost as a mechanism to drive emissions abatement. A disproportionate emphasis on revenue raising could lead to public opposition with carbon taxes being viewed as a ‘backdoor way’ to increase government budget.

The case for fiscal reform

There is talk in the final report around expanding carbon taxation by including additional sectors in the UK Emissions Trading Scheme. However, the Treasury largely misses the opportunity to build the foundations for a broader net-zero-aligned fiscal reform. The urgency of reorienting the economy with net-zero creates an opportunity to form a new, implicit social contract and thoroughly address politically charged areas, which include carbon pricing. A net-zero-aligned carbon price needs to be much higher than current levels and also applied consistently to drive all sectors of the economy towards net-zero.

The Treasury refrains from putting a number on a net-zero-aligned carbon price, highlighting numerous times that the analysis in the Net Zero Review is illustrative. This highlights the urgency for the Government to deliver its promised consultations to provide the necessary detail on a net-zero-aligned carbon pricing regime.

The final report acknowledges that carbon price signals across different sectors of the economy are uneven. Yet it points to policy objectives beyond decarbonisation that are in play to justify this, rather than communicating an intention to address it. One exception is the announced commitment to rebalancing policy costs from electricity to gas bills – this will be a crucial start to addressing the currently perverse price signals that are likely to hinder household decarbonisation. But as research shows, recovering low-carbon policy costs from energy bills will still, ultimately, be regressive.

Next steps

The Net Zero Review provides crucial proof that the Government is serious about maximising economic opportunities from net-zero while distributing costs and benefits in a fair way – even if gaps remain. The Review shows that every government department will be held accountable for ensuring that the net-zero policies they develop and implement are aligned with the principles of a just transition. The UK now needs to rapidly move from thinking to implementing its Net Zero Strategy in line with the principles in the Net Zero Review. That way it can sustain its position as a credible leader on climate action beyond COP26.