India’s sovereign green bonds: steps for building on a successful debut

By Neha Kumar, Head, South Asia Programme, Climate Bonds Initiative

Neha Kumar analyses the initial success of India’s new sovereign green bonds and suggests eight priorities for harnessing the momentum, in this post for the Sustainable Finance Leadership series.

India is the first major economy that will power its growth and drive its development transformation without substantial recourse to fossil fuels. Its efforts to decarbonise will have to accommodate the rising consumption needs of its people and go hand in hand with tackling the already locked-in impacts of climate change. This is a massive undertaking and will need concerted action to recalibrate and augment financial resources – public and private, domestic and international – so that it can frontload efforts to achieve its 2030 climate targets and forge a path to meeting net zero by 2070.

Many recent announcements, including the 2023–24 budget, signal increased policy stimulus and action on green growth – with emphasis on sustainable finance to deliver that growth. A key sustainable finance tool is the sovereign green bond, which made a successful debut in January, seeing India join 43 other governments that have raised green, social, sustainable, sustainability-linked (GSS+) debt. In just six years, they have raised up to US$323.7 billion and tapped into the rapidly growing global thematic bond market. From a few billion a decade ago to over $3.5 trillion now, this presents a huge opportunity to mobilise large-scale green investment. India mobilises green finance worth $44 billion annually, which is less than a quarter of what it requires to meet its 2030 targets, and it will need $3 trillion to plug the financing gap to reach net zero.

India’s sovereign issuance needs to be considered against this backdrop. The availability of accessible and affordable finance will determine the pace of green transition in India, the fifth largest and one of the fastest growing emerging economies in the world. The solutions India applies domestically and internationally will thus have a direct bearing on the collective fight against the climate crisis and achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Sovereign green debut performs better than expected

For sovereign issuers worldwide, two main motivations apply: diversification of the investor pool and the fillip the issuance gives to the growth of the local green/thematic bond markets. The ‘greenium’, which is the lower yield/return investors will accept for the green label, has a substantial positive signalling effect. The Indian sovereign green issuance scores well on these aspects.

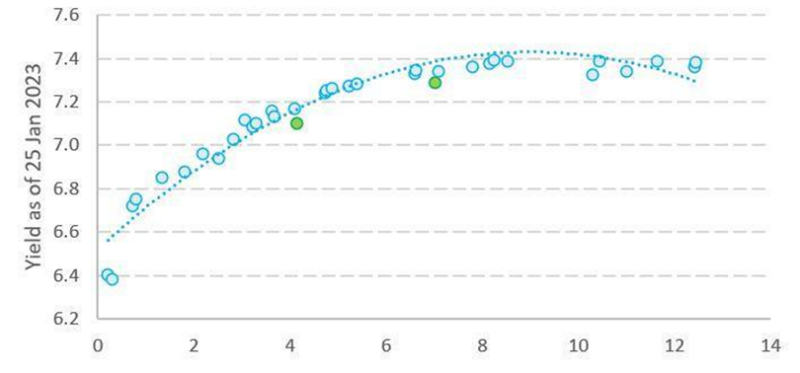

The sovereign green bonds were auctioned by the Reserve Bank of India in two tranches in January and February 2023, split equally between five and 10 year tenors. The bonds were oversubscribed by more than four times. Local insurers and public sector banks were the main investors, contradicting the long-held view that the demand base was non-existent. Equally encouraging was the participation of international investors in the INR [rupee] denominated onshore offering. They did so amid rising interest rates, sluggish global growth and depreciation of the rupee. The six basis point greenium (see Figure 1) secured against these suboptimal conditions is better than the predictions of most analysts. The greenium could grow in the future as the number and volume of issuances increase. Market reports suggest that the next sale of sovereign green bonds could be larger, up to $3 billion, and it is being planned for the first half of the 2023–24 financial year.

Figure 1. India 2027 and 2033 – greenium

Source: Climate Bonds Initiative

Demonstration effects will boost local green issuance

Hot on the heels of the sovereign issuance, the Indian state of Maharashtraannounced that it will raise $650 million through green bonds by 2024. It will be the first state to raise funds in this way. The early pick-up is quite encouraging, given states have a huge role to play in the energy transition, sustainable land use and increasing resilience to climate change impacts. Many states are already actively pursuing the green agenda and can readily explore thematic debt as part of their capital-raising plans.

There are also early signs of a pick-up in domestic issuances by public sector entities, municipal corporations and some large private sector issuers. Until now, the majority of Indian GSS+ bonds, which amount to $25 billion since 2015, have been in the offshore market and in hard currency, tapping the strong demand from international investors. The pace at which domestic issuance volume increases will be decided by how soon supportive regulations are introduced.

Integrity will be key to market growth

Investors care about integrity, and staying true to the label is important. The allocation in the debut has largely been for projects that can adhere to the best practice and widely applied international standards, such as grid scale and decentralised solar and wind generation projects, the green hydrogen mission, and metro lines.

The Ministry of Finance’s green bond framework encourages investment in energy efficiency, emission reduction, climate resilience and/or adaptation, biodiversity and ecosystems management. Its medium green rating, however, indicates that many project categories are loosely defined. All forthcoming issuances should continue to adhere to best practice on criteria for the evaluation and selection of projects. Pre- and post-issuance third-party verification, a growing norm among sovereign green bond issuers, can be adopted to reduce the chances of greenwashing and set a benchmark for the market. Transparency over the end-use of proceeds is shown to be rewarded by the market.

Eight steps towards charting a sustainable finance roadmap for India

The success of the sovereign green bonds can be used to outline immediate next steps towards charting a cogent sustainable finance roadmap:

- Introduce supportive regulations to expand domestic demand for thematic debt. The sovereign green bond debut has shown that domestic market demand could be galvanised through regulatory support. Insurers were allowed to count the purchase of green bonds against their usual investment mandates in government securities. This could now be extended to introduce mandates for pension and insurance companies to invest a certain percentage of their portfolio in thematic bonds, which could unlock billions of dollars in green capital flows. Life Insurance Company and the Employee Provident Fund Organisation, the two largest funds, have $605 billion in assets under management between them. Making green bonds eligible against Statutory Liquidity Ratio of banks should continue.

- Build a systematic programme of repeat sovereign issuances. This would add to investor confidence by enabling them to engage on future plans and build their portfolio. It could also help in streamlining processes for the Green Finance Working Committee and could add economies of scale to the compliance process and hence save avoidable costs.

- Foster a dialogue to grow local currency debt by emerging market sovereign issuers in the G20. Local currency onshore debt avoids currency mismatch and guards against volatility in international markets, thus protecting against external debt traps. It also allows smaller deals to access green finance, as offshore issuances are typically above $200 million. Following India’s success, Brazil, next to assume the G20 Presidency, plans to raise green bonds locally too. India could use the growing interest among emerging economies for local currency issuances and lead this initiative under the G20 priority on mobilising transition and green finance from local and global markets.

- Define and label sustainable activities through interoperable frameworks/taxonomies to guide capital flows. Definitions that can work seamlessly for global and local investors will help identify credible project pipelines and expenditures and aid a smoother flow of finance. Finance will be needed for all activities covering emission reduction, adaptation measures, sustained job creation and improving citizens’ access to resources. India could lead by putting forth such a definitional framework. The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) could also strengthen the linkages with international frameworks such as the International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) and Climate Bonds Standards in its guidelines.

- Repurpose national development banks (NDBs) that could unlock private capital for climate action and the SDGs. NDBs have deep knowledge of local markets and are well suited to understanding price risks, building credible pipelines, originating investment opportunities, and providing intermediate public and private domestic and international capital. NaBFID, India’s newly operational infrastructure development bank, could mobilise thematic debt onshore or offshore and channel it to diverse sectors. NABARD, SIDBI, Exim Bank and NHB – the other four development banks – could be active conduits for the green, resilient transition.

- Promote financial structures that help grow the pipeline. Blended finance solutions to de-risk investments, guarantees and partial guarantee systems that are accessible need to be part of the strategy, alongside platforms like investment trusts, real estate trusts and alternative investment funds, to extend credit and refinance portfolios of green assets. Currently, their scale is very small and processes too cumbersome.

- Build the capacity of government departments, regulators and the financial sector on transition plans, climate scenario analysis and disclosures. This would reduce the information asymmetry in the market, address data barriers and gaps, tag loans and expenditures, and help systematically realign portfolios and budgets to low-carbon and less risky lending and investment. New technical skills will be needed to aid the fast adoption of the Reserve Bank of India’s guidelines, regulations recently announced by SEBI, and widely-known voluntary standards such as ICMA and Climate Bonds Standards.

- Launch systematic outreach with domestic and international investors. Sovereign issuance has led to increased interest among investors. Proactive engagement to showcase pipelines and understand their expectations will be necessary to help grow onshore and offshore sales of INR offerings. Experience with the US dollar issuances by non-sovereign Indian entities shows that early engagement with international investors has a high rate of conversion to transactions.

Conclusions

India is on a cusp of change. In the midst of myriad challenges it has the opportunity to script an inclusive green transition with a cohesive roadmap to back it up. The steps outlined above can accelerate creation of a sustainable finance ecosystem that delivers at speed and scale. Three successive emerging economy G20 presidencies – India, plus Brazil and South Africa to come – can build on these initiatives to foster a sustainable finance architecture that aligns with the aspirations of the Global South.

The views in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Grantham Research Institute.