‘Double materiality’: what is it and why does it matter?

The concept of double materiality brings environmental impacts into the focus of standard-setting in accounting. Different reasons for adopting this concept might lead to widely varying interpretations, yet the fitness of the financial system to facilitate a net-zero economy depends on how it is conceived. Matthias Täger explains.

Finance has become a key arena for climate action over recent years. Investors are teaming up in alliances advocating for net-zero carbon emissions, and nearly 90 central banks and financial supervisors have come together in the Network for Greening the Financial System. Financial institutions have caught the attention of environmental activists like Extinction Rebellion too, as they set their sights beyond the fossil fuel giants.

Broadly speaking, climate-related activities within finance fall somewhere along the spectrum between aligning investment activity with climate goals and managing climate-related risks (from extreme weather events or rising carbon prices, for example).

Lack of data – lack of decisions

No matter where on the spectrum any one institution sits, they all voice one similar complaint: there is a lack of granular, high-quality, useful data. Without that data, financial actors often feel unable to make climate-related decisions, even if they wanted to. This has prompted both debates and actions by financial supervisors and regulators in terms of adapting disclosure requirements to plug the data gap. The Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is the most global and prominent example. More recently, the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS), which sets accounting standards for approximately 120 nations, announced it was throwing its weight behind the task of bringing sustainability into financial disclosure. In this context of sustainability-related financial disclosure, a new concept has emerged: double materiality.

What is double materiality?

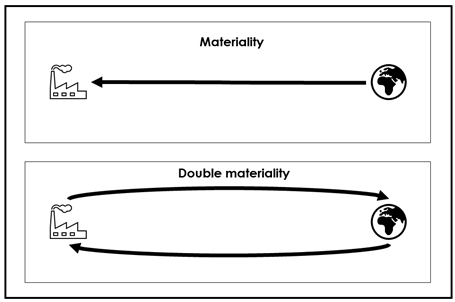

Double materiality is an extension of the key accounting concept of materiality of financial information. Information on a company is material and should therefore be disclosed if “a reasonable person would consider it [the information] important”, according to the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Thanks to the work by the TCFD, it is now widely accepted within financial markets that climate-related impacts on a company can be material and therefore require disclosure.

The concept of double materiality takes this notion one step further: it is not just climate-related impacts on the company that can be material but also impacts of a company on the climate – or any other dimension of sustainability, for that matter (often subsumed under the environmental, social and governance, or ESG, label).

This notion of materiality is already embedded in the EU’s new sustainable finance disclosure regime for financial firms and corporates. Additionally, Mark Carney, former Chair of the FSB, is now, as UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, pushing for worldwide mandatory climate disclosure ahead of the COP26 climate summit, elevating the concept of double materiality to a matter of global concern.

Drilling down on the meaning

While the basic definition of double materiality is widely accepted, its meaning is still up for debate. Yes, in principle the impacts of a company or a portfolio on the climate or the wider environment can be material – but how do we know what exactly is a material impact? The answer to this question fundamentally depends on one’s view of why information on environmental impacts could be material in the first place:

- Either because environmental impacts could translate into financial risks, e.g. through legal liabilities or negative effects on a company’s reputation, etc. (a weak conception of double materiality)

- Or because a ‘reasonable person’ might consider the information material for reasons other than direct financial repercussions (a strong conception of double materiality).

Where the latter conception is concerned, there certainly are plenty of reasons. For instance, an investor might want to follow a specific investment policy containing clauses on environmental impacts. Investors with long time horizons or universal owners might want to base their investment decisions on the principle of prudence and not contribute to the destabilisation of the climate system, which would in turn destabilise the financial system. The question of what double materiality means thus turns into a question of who the ‘reasonable person’ is, and what their interests are, which in turn define what counts as material, i.e. important, to them.

Disclosure for whom?

Over the past few decades, financial disclosure standards have focused on the alleged information needs of a single stylised textbook investor, sidelining other possible and actual information needs. The rise of double materiality presents an opportunity to correct this design flaw. Financial disclosures could be made decision-useful again to the growing number of investors who seek to align their investment practices with climate or wider sustainability goals – whether due to specific mission statements or the enlightened self-interest that there is no profit on a dead planet.

Equally important would be to cater for the information needs of other users of financial statements: from employees and labour unions to local communities and authorities. These key stakeholders all make significant investments in companies in a wider sense – whether in terms of time or infrastructure spending, for example, and are therefore relevant user groups.

Providing a stylised, imagined investor persona with high-quality, audited information while leaving countless actual investors and other key stakeholders reading through sometimes hundreds of pages of non-standardised and unaudited sustainability reports constitutes nothing less but a market governance failure.

Why does this debate matter?

Disclosure standards and by extension the interpretation of double materiality matter on three other levels:

- Interest formation. The artificially uniform understanding of what information a user of financial statements needs sabotages the ability of diverse market participants to form opinions and make informed decisions. Thus, the smooth and free functioning of markets is actively disrupted – by design.

- Market dynamics. Accounting standards are not neutral, but they systematically affect capital allocation and market dynamics. Decades of global standard harmonisation have veiled the fact that accounting practices are simply social conventions and not exact or objective measures. In 1993, for instance, the German car manufacturer Daimler disclosed 615 million Deutsche Mark in net profits under German accounting rules but a loss of 1.84 billion Deutsche Mark under US rules. Accounting rules can therefore substantially alter the perception of a company in the eyes of financial markets and incentivise certain management practices (e.g. distributing profits to shareholders) over others (e.g. reinvesting profits). They might even exacerbate financial crises; fair value accounting, for instance, has been criticised for having pro-cyclical effects during the 2008 financial crisis. Thus, far from being neutral, accounting standards shape capital allocation dynamics. Their implications for facilitating or preventing climate-aligned investment therefore deserve close attention.

- Corporate management. Finally, disclosure requirements can directly affect corporate behaviour too. After all, what gets measured gets managed. The right disclosure standards can facilitate effective management of, for example, emissions and other environmental impacts within reporting entities.

As an abstract concept, double materiality still needs to be filled with life. Its actual meaning will most likely remain contested for a while. Whether its weak or its strong conception will guide accounting standard-setting in the future is critical. The IFRS is expected to make a decision in this matter just in time for COP26, in a pivotal first moment of truth. The fitness of the financial system to facilitate a net-zero economy depends on it.